The final part, starting with a reaction of Mochizuki himself on my previous IUTeich-posts.

July 7th, 2013

Mochizuki update

While i’ve been away from G+, someone emailed Mochizuki my last post on the problem i have with Frobenioids1. He was kind enough to forward me M’s reply:

“There is absolutely nothing difficult or subtle going on here (e.g., by comparison to the portion of the theory cited in the discussion preceding the statement of this “problem”!). The nontrivial result is the fact that the degree is rational, i.e., the initial portion of [FrdI], Theorem 6.4, (iii), which is a consequence of a highly nontrivial result in transcendence theory due to Lang (i.e., [FrdI], Lemma 6.5, (ii)). Once one knows this rationality, the conclusion that distinct prime numbers are not confused with one another is a formal consequence (i.e., no complicated subtle arguments!) of the fact that the ratio of the natural logarithm of any two distinct prime numbers is never rational.

Sincerely, Shinichi Mochizuki”

Being back, i’ll give it another go.

Having read the shared article below (2/5/2019 ‘the paradox of the proof’), it’s comforting to know that other people, including +Aise Johan de Jong and +Cathy O’Neil, are also frustrated by M’s opaque latest writings.

July 11th, 2013

Mochizuki’s Frobenioid reconstruction: the final bit

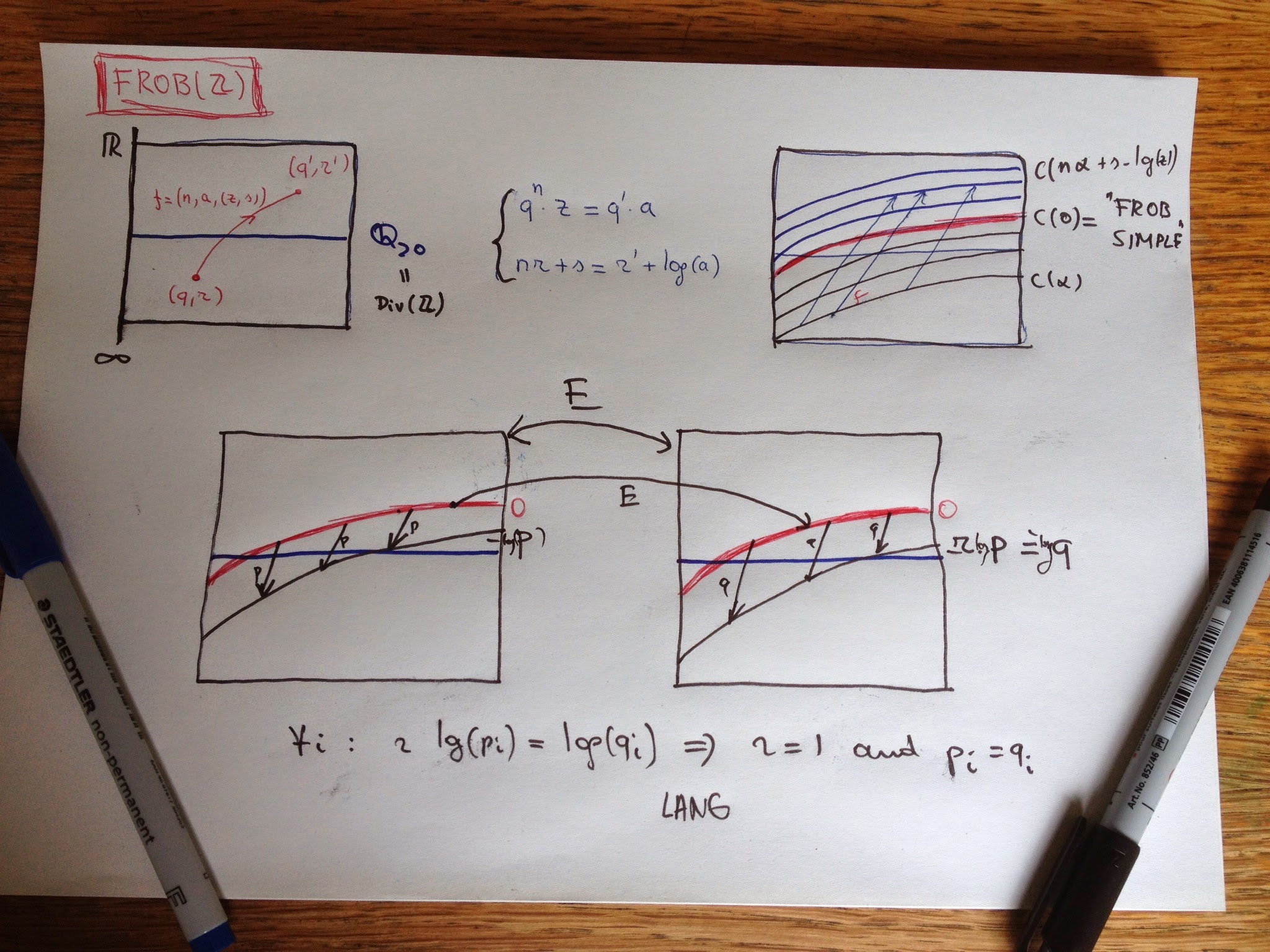

In “The geometry of Frobenioids 1” Mochizuki ‘dismantles’ arithmetic schemes and replaces them by huge categories called Frobenioids. Clearly, one then wants to reconstruct the schemes from these categories and we almost understood how he manages to to this, modulo the ‘problem’ that there might be auto-equivalences of $Frob(\mathbb{Z})$, the Frobenioid corresponding to $\mathbf{Spec}(\mathbb{Z})$ i.e.the collection of all prime numbers, reshuffling distinct prime numbers.

In previous posts i’ve simplified things a lot, leaving out the ‘Arakelov’ information contained in the infinite primes, and feared that this lost info might be crucial to understand the final bit. Mochizuki’s email also points in that direction.

Here’s what i hope to have learned this week:

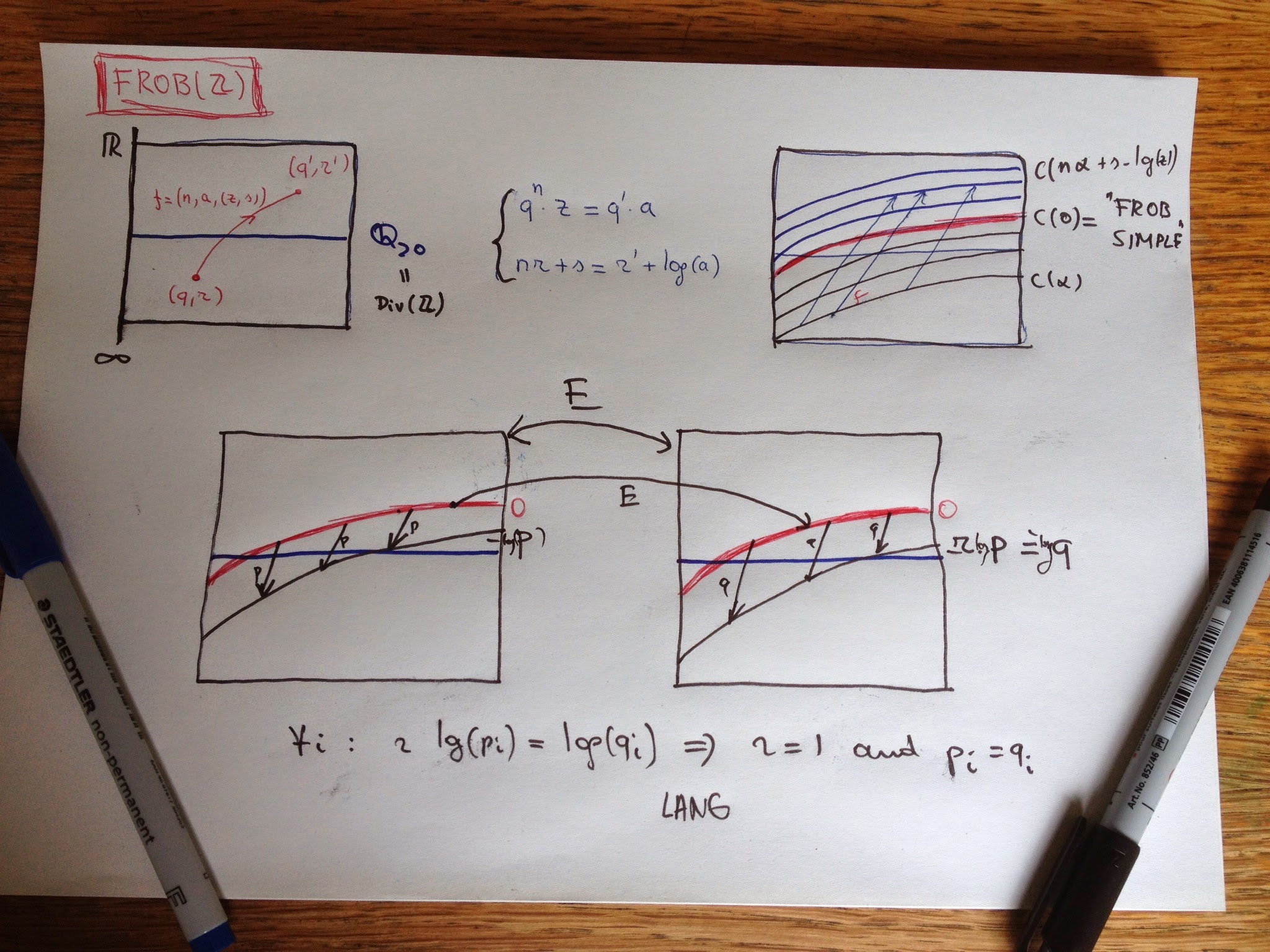

the full Frobenioid $Frob(\mathbb{Z})$

objects of $Frob(\mathbb{Z})$ consist of pairs $(q,r)$ where $q$ is a strictly positive rational number and $r$ is a real number.

morphisms are of the form $f=(n,a,(z,s)) : (q,r) \rightarrow (q’,r’)$ (where $n$ and $z$ are strictly positive integers, $a$ a strictly positive rational number and $s$ a positive real number) subject to the relations that

\[

q^n.z = q’.a \quad \text{and} \quad n.r+s = r’+log(a) \]

$n$ is called the Frobenious degree of $f$ and $(z,s)$ the divisor of $f$.

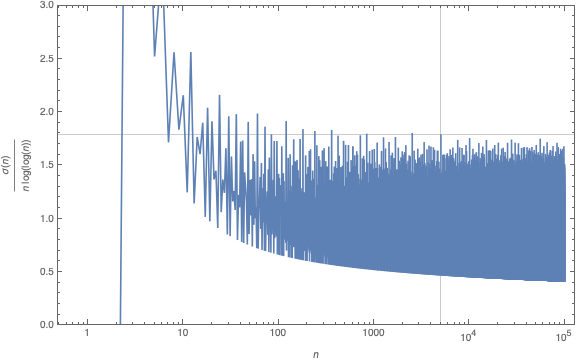

All this may look horribly complicated until you realise that the isomorphism classes in $Frob(\mathbb{Z})$ are exactly the ‘curves’ $C(\alpha)$ consisting of all pairs $(q,r)$ such that $r-log(q)=\alpha$, and that morphisms with the same parameters as $f$ send points in $C(\alpha)$ to points in $C(\beta)$ where

\[

\beta = n.\alpha + s – log(a) \]

So, the isomorphism classes can be identified with the real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ and special linear morphisms of type $(1,a,(1,s))$ and their compositions are compatible with the order-structure and addition on $\mathbb{R}$.

Crucial is Mochizuki’s observation that $C(0)$ are precisely the ‘Frobenious-trivial’ objects in $Frob(\mathbb{Z})$ (i’ll spare you the details but it is a property on having sufficiently many nice endomorphisms).

Now, consider an auto-equivalence $E$ of $Frob(\mathbb{Z})$. It will induce a map between the isoclasses $E : \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ which is additive and as Frob-trivs are mapped under $E$ to Frob-trivs this will map $0$ to $0$, so $E$ will be an additive group-endomorphism on $\mathbb{R}$ hence of the form $x \rightarrow r.x$ for some fixed real number $r$, and we want to show that $r=1$.

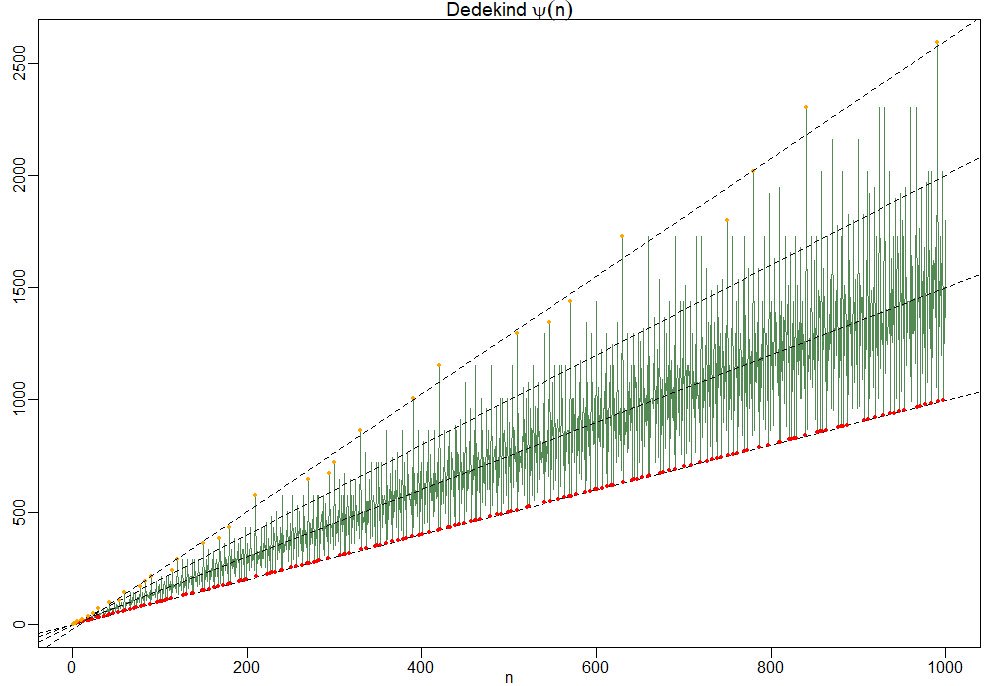

Linear irreducible morphisms are of type $(1,a,(p,0))$ where $p$ is a prime number and they map $C(\alpha)$ to $C(\alpha-log(p))$. As irreducibles are preserved under equivalence this means that for each prime $p$ there must exist a prime $q$ such that $r log(p) = log(q)$.

Now if $r$ is an irrational number, there must be at least three triples $(p_1,q_1),(p_2,q_2)$ and $(p_3,q_3)$ satisfying $r log(p_i) = log(q_i)$ but this contradicts a fairly hard result, due to Lang, that for 6 distinct primes l_1,…,l_6 there do not exist positive rational numbers $a,b$ such that

\[

log(l_1)/log(l_2) = a log(l_3)/log(l_4) = b log(l_5)/log(l_6) \]

So, $r$ must be rational and of the form $n/m$, but then $r=1$ (if not the correspondence $r.log(p) = log(q)$ gives $p^n=q^m$ contradicting unique factorisation). This then shows that under the auto-equivalence each prime $p$ (corresponding to a linear irreducible map) is send to itself.

This was the remaining bit left to show that the Frobenioid corresponding to any Galois extension of the rationals contains enough information to reconstruct from it the schemes of all rings of integers in intermediate fields.

August 15th, 2013

Szpiro’s Marabout-Flash on number theory

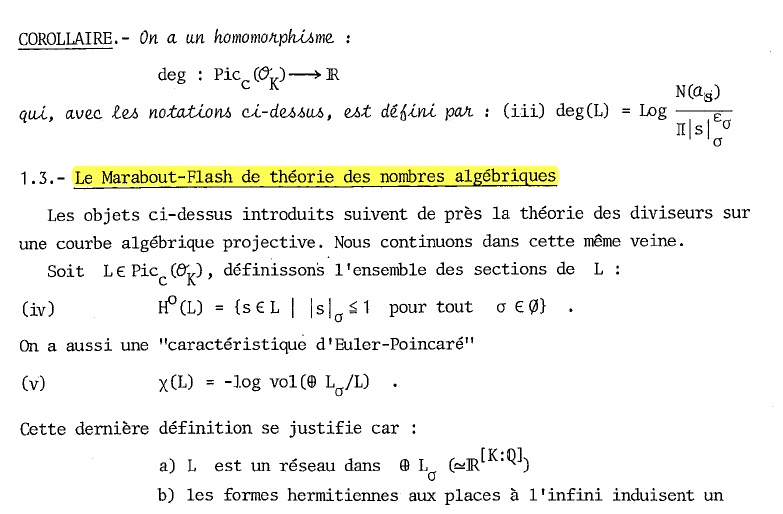

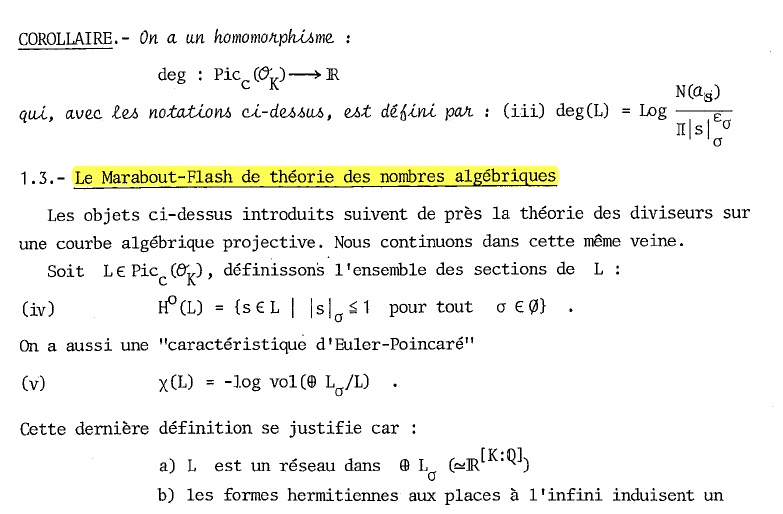

For travellers into Mochizuki-territory the indispensable rough guide is Lucien Szpiro’s ‘Marabout-Flash de théorie des nombres algébriques’, aka section I.1.3 in ‘Séminaire sur les pinceaux arithmétiques: la conjecture de Mordell’.

Marabout Flash was a Franco-Belge series of do-it-yourself booklets, quite popular in the 60ties and 70ties, on almost every aspect of everyday’s life.

In just a couple of pages Szpiro describes how one can extend the structure sheaf of a fractional ideal of a ring of integers to a ‘metrized’ (or Arakelov) line-bundle on the completed prime spectrum (including the infinite places). These bundles then satisfy properties similar to those of line-bundles on smooth projective curves, including a version of the Riemann-Roch theorem and a criterium to have non-zero global sections.

These (fairly simple) results then quickly lead to proofs of the first major results in number theory such as the Hermite-Minkowski theorem and Dirichlet’s unit theorem.

December 29th, 2014

Mochizuki in denial

From M’s 2014 IUTeich-Progress-Report (17 pages, the 2013-edition was only 7 pages long):

“Activities surrounding IUTeich appears to be in a stage of transition from a focus on verification to a focus on dissemination.”

If only…

He further lists hypotheses as to why nobody (apart from his 3 disciples Yamashita,Saidi and Hoshi) makes a serious effort to “study the theory carefully and systematically from the beginning”:

1. it is too long (1500-2500 pages)

2. there’s lack of textbooks on anabelian geometry

3. we are obsessed with the Langlands program

4. there’s little room for generalisations

5. it may not be directly useful for our own research

But then, why should anyone make such an effort, as:

“With the exception of the handful of researchers already involved in the verification activities concerning IUTeich, every researcher in arithmetic geometry throughout the world is a complete novice with respect to the mathematics surrounding IUTeich, and hence, in particular, is simply not qualified to issue a definite judgment concerning the validity of IUTeich on the basis of a ‘deep understanding’ arising from his/her previous research achievements.”

No Mochizuki, the next phase will not be dissemination, it will be denial.

Other remarkable sentences are:

“IUTeich is ‘the correct theory’ in the sense that it leads one to doubt the existence of any sort of ‘alternative proof’, i.e. via essentially different techniques, of the ABC Conjecture.”

and:

“the status of IUTeich in the field of arithmetic geometry constitutes a sort of faithful miniature model of the status of pure mathematics in human society.”

Already looking forward to the 2015 ‘progress’ report…

October 8th, 2015

Proud to be working at a well-known university

First time I’m mentioned in “Nature”, they issue this correction:

Corrected: An earlier version of this story incorrectly located the University of Antwerp in the Netherlands. It is in Belgium. The text has been updated.

Not particularly proud of the quote they took from my blog though:

“Is it just me, or is Mochizuki really sticking up his middle finger to the mathematical community”.

December 17th, 2017

We’re heading for a bad ending

Yesterday, my feeds became congested by (Japanese) news saying that Mochizuki’s (claimed) proof of the abc-conjecture had been vetted and considered fit to be published in a respectable journal.

Today, long term supporters of M’s case began their Echternachian-retreat after finding out that Mochizuki himself is the editor in charge of that respectable journal.

Attached is Ed Frenkel’s retraction of his previous tweet. Also, Taylor Dupuy deemed the latest action a bridge too far, see here.

Peter Woit did a great job in his recent post

pinpointing a critical argument in the 500-page long papers having as its “proof” that it followed trivially from the definitions…

I’d expect any board of editors to resign in such a case.

I fear this can only end badly.

.jpg)