In the topology of dreams we looked at Sibony’s idea to view dream-interpretations as sections in a fibered space.

The ‘points’ in the base-space and fibers consisting of chunks of text, perhaps connected by links. The topology and shape of this fibered space is still shrouded in mystery.

Let’s look at a simple approach to turn a large number of texts into a topos, and define a loose metric on it.

There’s this paper An enriched category theory of language: from syntax to semantics by Tai-Danae Bradley, John Terilla and Yiannis Vlassopoulos.

Tai-Danae Bradley is an excellent communicator of everything category related, so probably it is more fun to read her own blogposts on this paper:

- Language, Statistics, & Category Theory, Part 1

- Language, Statistics, & Category Theory, Part 2

- Language, Statistics, & Category Theory, Part 3

or to watch her Categories for AI talk: ‘Category Theory Inspired by LLMs’:

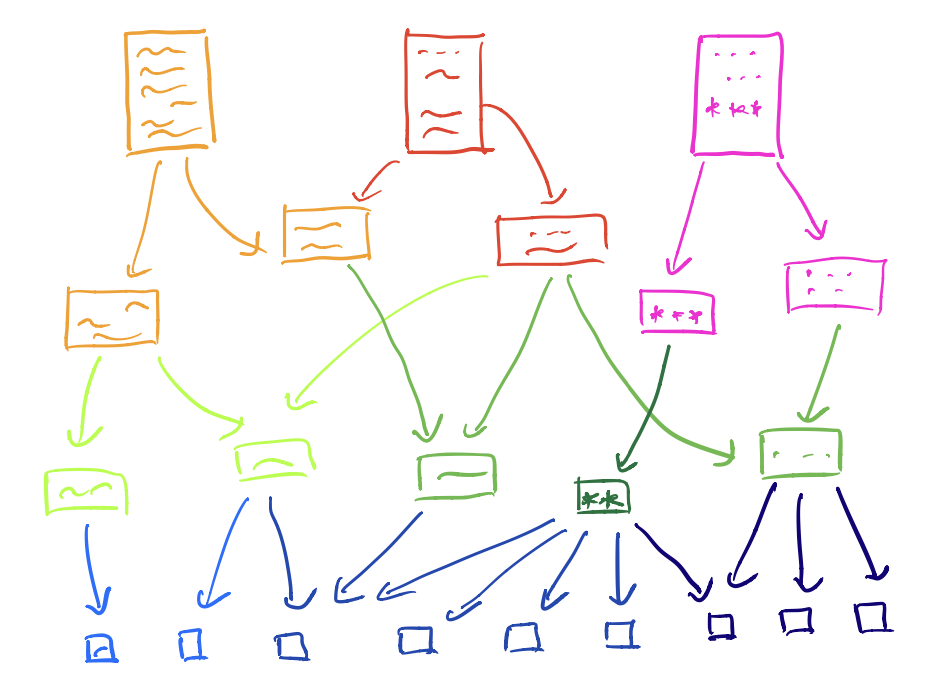

Let’s start with a collection of notes. In the paper, they consider all possible texts written in some language, but it may be a set of webpages to train a language model, or a set of recollections by someone.

Next, shred these notes into chunks of text, and point one of these to all the texts obtained by deleting some words at the start and/or end of it. For example, the note ‘a red rose’ will point to ‘a red’, ‘red rose’, ‘a’, ‘red’ and ‘rose’ (but not to ‘a rose’).

You may call this a category, to me it is just as a poset $(\mathcal{L},\leq)$. The maximal elements are the individual words, the minimal elements are the notes, or websites, we started from.

A down-set $A$ of this poset $(\mathcal{L},\leq)$ is a subset of $\mathcal{L}$ closed under taking smaller elements, that is, if $a \in A$ and $b \leq a$, then $b \in A$.

The intersection of two down-sets is again a down-set (or empty), and the union of down-sets is again a downset. That is, down-sets define a topology on our collection of text-snippets, or if you want, on language-fragments.

For example, the open determined by the word ‘red’ is the collection of all text-fragments containing this word.

The corresponding presheaf topos $\widehat{\mathcal{L}}$ is then just the category of all (set-valued) presheaves on this topological space.

As an example, the Yoneda-presheaf $\mathcal{Y}(p)$ of a text-snippet $p$ is the contra-variant functor

$$(\mathcal{L},\leq) \rightarrow \mathbf{Sets}$$

sending any $q \leq p$ to the unique map $\ast$ from $q$ to $p$, and if $q \not\leq p$ then we map it to $\emptyset$. If $A$ is a down-set (an open of over topological space) then the sections of $\mathcal{Y}(p)$ over $A$ are $\{ \ast \}$ if for all $a \in A$ we have $a \leq p$, and $\emptyset$ otherwise.

The presheaf $\mathcal{Y}(p)$ already contains some semantic information about the snippet $p$ as it gives all contexts in which $p$ appears.

Perhaps interesting is that the ‘points’ of the topos $\widehat{\mathcal{L}}$ are the notes we started from.

Recall that Connes and Gauthier-Lafaey want to construct a topos describing someone’s unconscious, and points of that topos should be the connection with that person’s consciousness.

Suppose you want to unravel your unconscious. You start by writing down a large set of notes containing all relevant facts of your life. Then you construct from these notes the above collection of snippets and its corresponding pre-sheaf topos. Clearly, you wrote your notes consciously, but probably the exact phrasing of these notes, or recurrent themes in them, or some text-combinations are ruled by your unconscious.

Ok, it’s not much, but perhaps it’s a germ of an potential approach…

(Image credit)

Now we come to the interesting part of the paper, the ‘enrichment’ of this poset.

Surely, some of these text-snippets will occur more frequently than others. For example, in your starting notes the snippet ‘red rose’ may appear ten time more than the snippet ‘red dwarf’, but this is not visible in the poset-structure. So how can we bring in this extra information?

If we have two text-snippets $p$ and $q$ and $q \leq p$, that is, $p$ is a connected sub-string of $q$. We can compute the conditional probability $\pi(q|p)$ which tells us how likely it is that if we spot an occurrence of $p$ in our starting notes, it is part of the larger sentence $q$. These numbers can be easily computed and from the rules of probability we get that for snippets $r \leq q \leq p$ we have that

$$\pi(r|p) = \pi(r|q) \times \pi(q|r)$$

so these numbers (all between $0$ and $1$) behave multiplicative along paths in the poset.

Nice in theory, but it requires an awful lot of computation. From the paper:

The reader might think of these probabilities $\pi(q|p)$ as being most well defined when $q$ is a short extension of $p$. While one may be skeptical about assigning a probability distribution on the set of all possible texts, it’s reasonable to say there is a nonzero probability that cat food will follow I am going to the store to buy a can of and, practically speaking, that probability can be estimated.

Indeed, existing LLMs successfully learn these conditional probabilities $\pi(q|p)$ using standard machine learning tools trained on large corpora of texts, which may be viewed as providing a wealth of samples drawn from these conditional probability distributions.

It may be easier to have an estimate $\mu(q|p)$ of this conditional probability for immediate successors (that is, if $q$ is obtained from $p$ by adding one word at the beginning or end of it), and then extend this measure to all arrows in the poset by taking the maximum of products along paths. In this way we have for all $r \leq q \leq p$ that

$$\mu(r|p) \geq \mu(r|q) \times \mu(q|p)$$

The upshot is that this measure $\mu$ turns our poset (or category) $(\mathcal{L},\leq)$ into a category ‘enriched’ over the unit interval $[ 0,1 ]$ (suitably made into a monoidal category).

I’ll spare you the details, just want to flash out the corresponding notion of ‘enriched presheaves’ which are the objects of the semantic category $\widehat{\mathcal{L}}^s$ in the paper, which is the enriched version of the presheaf category $\widehat{\mathcal{L}}$.

An enriched presheaf is a function (not functor)

$$F~:~\mathcal{L} \rightarrow [0,1]$$

satisfying the condition that for all text-snippets $r,q \in \mathcal{L}$ we have that

$$\mu(r|q) \leq [F(q),F(r)] = \begin{cases} \frac{F(r)}{F(q)}~\text{if $F(r) \leq F(q)$} \\ 1~\text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

Note that the enriched (or semantic) Yoneda presheaf $\mathcal{Y}^s(p)(q) = \mu(q|p)$ satisfies this condition, and now this data not only records the contexts in which $p$ appears, but also measures how likely it is for $p$ to appear in a certain context.

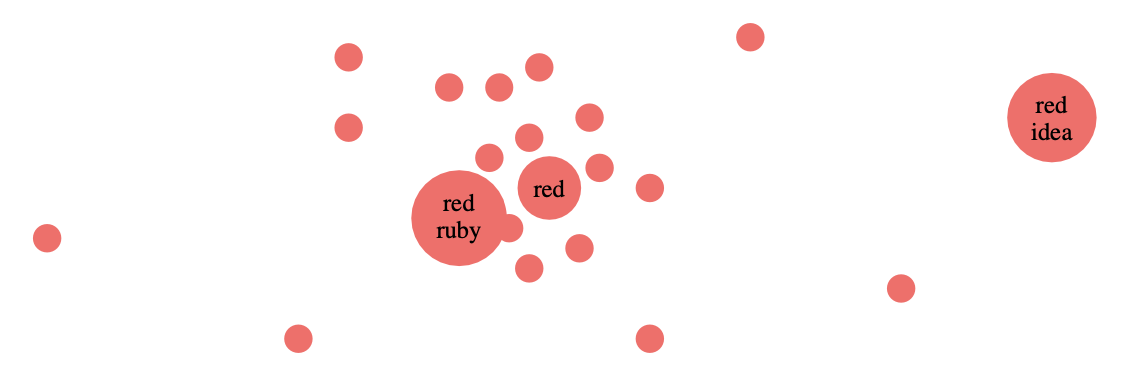

Another cute application of the condition on the measure $\mu$ is that it allows us to define a ‘distance function’ (satisfying the triangle inequality) on all text-snippets in $\mathcal{L}$ by

$$d(q,p) = \begin{cases} -ln(\mu(q|p))~\text{if $q \leq p$} \\

\infty~\text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

So, the higher $\mu(q|p)$ the closer $q$ lies to $p$, and now the snippet $p$ (example ‘red’) not only defines the open set in $\mathcal{L}$ of all texts containing $p$, but now we can structure the snippets in this open set with respect to this ‘distance’.

In this way we can turn any language, or a collection of texts in a given language, into what Lawvere called a ‘generalized metric space’.

It looks as if we are progressing slowly in our, probably futile, attempt to understand Alain Connes’ and Patrick Gauthier-Lafaye’s claim that ‘the unconscious is structured like a topos’.

Even if we accept the fact that we can start from a collection of notes, there are a number of changes we need to make to the above approach:

- there will be contextual links between these notes

- we only want to retain the relevant snippets, not all of them

- between these ‘highlights’ there may also be contextual links

- texts can be related without having to be concatenations

- we need to implement changes when new notes are added

- … (much more)

Perhaps, we should try to work on a specific ‘case’, and explore all technical tools that may help us to make progress.

(tbc)

Previously in this series:

Next:

Comments closed