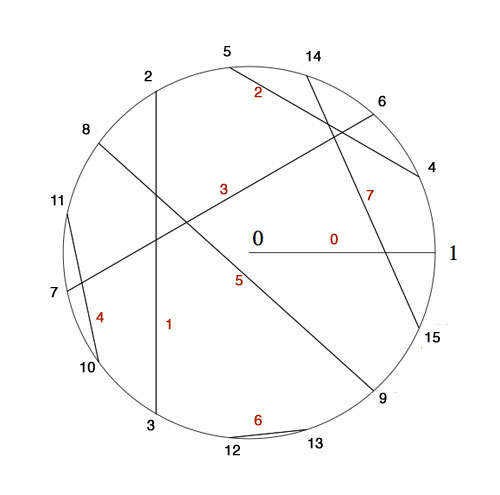

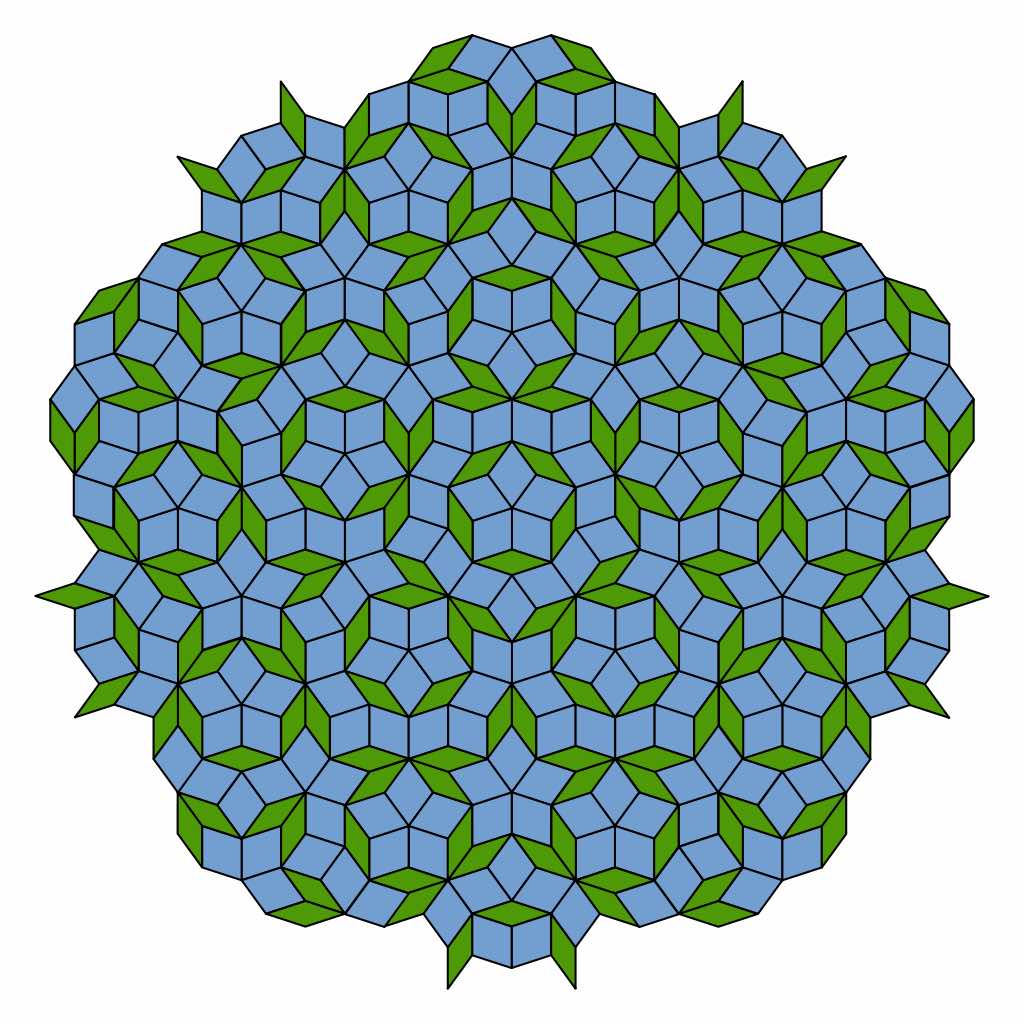

Penrose tilings are aperiodic tilings of the plane, made from 2 sort of tiles : kites and darts. It is well known (see for example the standard textbook tilings and patterns section 10.5) that one can describe a Penrose tiling around a given point in the plane as an infinite sequence of 0’s and 1’s, subject to the condition that no two consecutive 1’s appear in the sequence. Conversely, any such sequence is the sequence of a Penrose tiling together with a point. Moreover, if two such sequences are eventually the same (that is, they only differ in the first so many terms) then these sequences belong to two points in the same tiling,

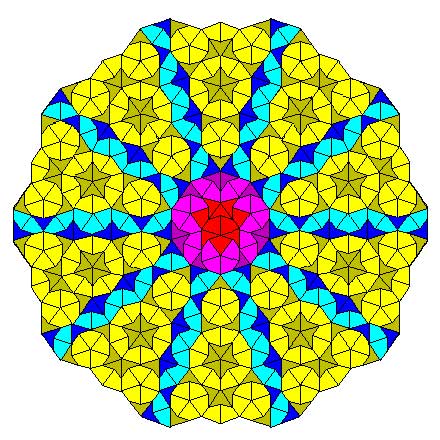

Another remarkable feature of Penrose tilings is their local isomorphism : fix a finite region around a point in one tiling, then in any other Penrose tiling one can find a point having an isomorphic region around it. For this reason, the space of all Penrose tilings has horrible topological properties (all points lie in each others closure) and is therefore a prime test-example for the techniques of noncommutative geometry.

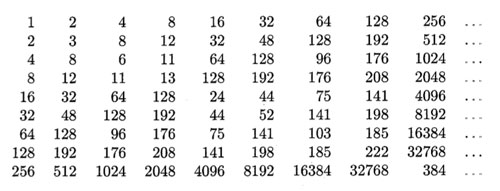

In his old testament, Noncommutative Geometry, Alain Connes associates to this space a $C^*$-algebra $Fib$ (because it is constructed from the Fibonacci series $F_0,F_1,F_2,…$) which is the direct limit of sums of two full matrix-algebras $S_n$, with connecting morphisms

$S_n = M_{F_n}(\mathbb{C}) \oplus M_{F_{n-1}}(\mathbb{C}) \rightarrow S_{n+1} = M_{F_{n+1}}(\mathbb{C}) \oplus M_{F_n}(\mathbb{C}) \qquad (a,b) \mapsto ( \begin{matrix} a & 0 \\ 0 & b \end{matrix}, a)$

As such $Fib$ is an AF-algebra (for approximately finite) and hence formally smooth. That is, $Fib$ would be the coordinate ring of a smooth variety in the noncommutative sense, if only $Fib$ were finitely generated. However, $Fib$ is far from finitely generated and has other undesirable properties (at least for a noncommutative algebraic geometer) such as being simple and hence in particular $Fib$ has no finite dimensional representations…

A couple of weeks ago, Paul Smith discovered a surprising connection between the noncommutative space of Penrose tilings and an affine algebra in the paper The space of Penrose tilings and the non-commutative curve with homogeneous coordinate ring $\mathbb{C} \langle x,y \rangle/(y^2)$.

A couple of weeks ago, Paul Smith discovered a surprising connection between the noncommutative space of Penrose tilings and an affine algebra in the paper The space of Penrose tilings and the non-commutative curve with homogeneous coordinate ring $\mathbb{C} \langle x,y \rangle/(y^2)$.

Giving $x$ and $y$ degree 1, the algebra $P = \mathbb{C} \langle x,y \rangle/(y^2)$ is obviously graded and noncommutative projective algebraic geometers like to associate to such algebras their ‘proj’ which is the quotient category of the category of all graded modules in which two objects become isomorphisc iff their ‘tails’ (that is forgetting the first few homogeneous components) are isomorphic.

The first type of objects NAGers try to describe are the point modules, which correspond to graded modules in which every homogeneous component is 1-dimensional, that is, they are of the form

$\mathbb{C} e_0 \oplus \mathbb{C} e_1 \oplus \mathbb{C} e_2 \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathbb{C} e_n \oplus \mathbb{C} e_{n+1} \oplus \cdots$

with $e_i$ an element of degree $i$. The reason for this is that point-modules correspond to the points of the (usual, commutative) projective variety when the affine graded algebra is commutative.

Now, assume that a Penrose tiling has been given by a sequence of 0’s and 1’s, say $(z_0,z_1,z_2,\cdots)$, then it is easy to associate to it a graded vectorspace with action given by

$x.e_i = e_{i+1}$ and $y.e_i = z_i e_{i+1}$

Because the sequence has no two consecutive ones, it is clear that this defines a graded module for the algebra $P$ and determines a point module in $\pmb{proj}(P)$. By the equivalence relation on Penrose sequences and the tails-equivalence on graded modules it follows that two sequences define the same Penrose tiling if and only if they determine the same point module in $\pmb{proj}(P)$. Phrased differently, the noncommutative space of Penrose tilings embeds in $\pmb{proj}(P)$ as a subset of the point-modules for $P$.

The only such point-module invariant under the shift-functor is the one corresponding to the 0-sequence, that is, corresponds to the cartwheel tiling

Another nice consequence is that we can now explain the local isomorphism property of Penrose tilings geometrically as a consequence of the fact that the $Ext^1$ between any two such point-modules is non-zero, that is, these noncommutative points lie ‘infinitely close’ to each other.

This is the easy part of Paul’s paper.

The truly, truly amazing part is that he is able to recover Connes’ AF-algebra $Fib$ from $\pmb{proj}(P)$ as the algebra of global sections! More precisely, he proves that there is an equivalence of categories between $\pmb{proj}(P)$ and the category of all $Fib$-modules $\pmb{mod}(Fib)$!

In other words, the noncommutative projective scheme $\pmb{proj}(P)$ is actually isomorphic to an affine scheme and as its coordinate ring is formally smooth $\pmb{proj}(P)$ is a noncommutative smooth variety. It would be interesting to construct more such examples of interesting AF-algebras appearing as local rings of sections of proj-es of affine graded algebras.

Comments closed