The Knight-seating problems asks for a consistent placing of n-th Knight at an odd root of unity, compatible with the two different realizations of the algebraic closure of the field with two elements.

The first identifies the multiplicative group of its non-zero elements with the group of all odd complex roots of unity, under complex multiplication. The second uses Conway’s ‘simplicity rules’ to define an addition and multiplication on the set of all ordinal numbers.

The odd Knights of the round table-problem asks for a specific one-to-one correspondence between two realizations of ‘the’ algebraic closure $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ of the field of two elements.

The first identifies the multiplicative group of its non-zero elements with the group of all odd complex roots of unity, under complex multiplication. The addition on $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ is then recovered by inducing an involution on the odd roots, pairing the one corresponding to x to the one corresponding to x+1.

The second uses Conway’s ‘simplicity rules’ to define an addition and multiplication on the set of all ordinal numbers. Conway proves in ONAG that this becomes an algebraically closed field of characteristic two and that $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ is the subfield of all ordinals smaller than $\omega^{\omega^{\omega}} $. The finite ordinals (the natural numbers) form the quadratic closure of $\mathbb{F}_2 $.

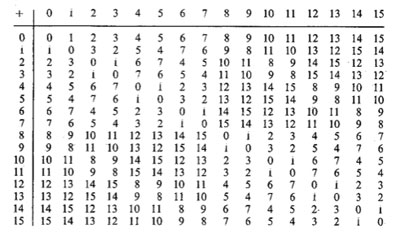

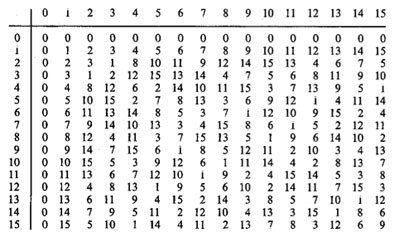

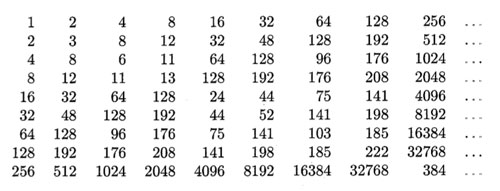

On the natural numbers the Conway-addition is binary addition without carrying and Conway-multiplication is defined by the properties that two different Fermat-powers $N=2^{2^i} $ multiply as they do in the natural numbers, and, Fermat-powers square to its sesquimultiple, that is $N^2=\frac{3}{2}N $. Moreover, all natural numbers smaller than $N=2^{2^{i}} $ form a finite field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^i}} $. Using distributivity, one can write down a multiplication table for all 2-powers.

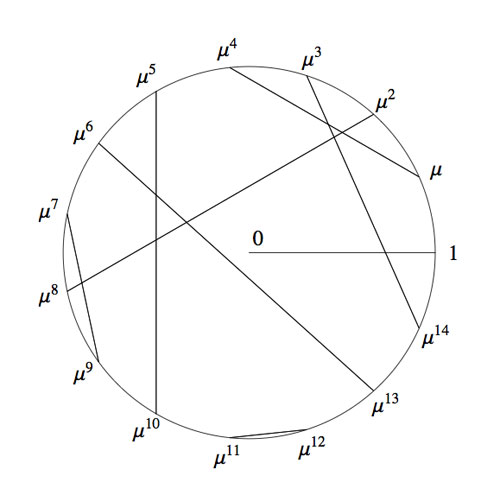

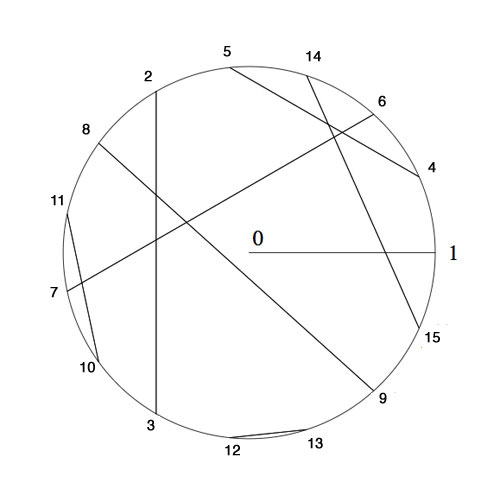

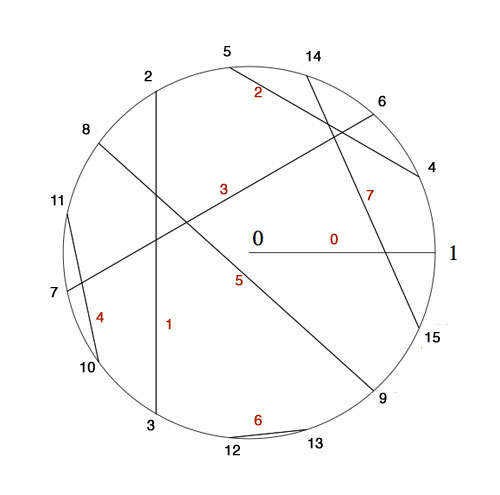

The Knight-seating problems asks for a consistent placing of n-th Knight $K_n $ at an odd root of unity, compatible with the two different realizations of $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $. Last time, we were able to place the first 15 Knights as below, and asked where you would seat $K_{16} $

$K_4 $ was placed at $e^{2\pi i/15} $ as 4 was the smallest number generating the ‘Fermat’-field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^2}} $ (with multiplicative group of order 15) subject to the compatibility relation with the generator 2 of the smaller Fermat-field $\mathbb{F}_2 $ (with group of order 15) that $4^5=2 $.

To include the next Fermat-field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^3}} $ (with multiplicative group of order 255) consistently, we need to find the smallest number n generating the multiplicative group and satisfying the compatibility condition $n^{17}=4 $. Let’s first concentrate on finding the smallest generator : as 2 is a generator for 1st Fermat-field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^1}} $ and 4 a generator for the 2-nd Fermat-field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^2}} $ a natural conjecture might be that 16 is a generator for the 3-rd Fermat-field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^3}} $ and, more generally, that $2^{2^i} $ would be a generator for the next field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^{i+1}}} $.

However, an “exercise” in the 1978-paper by Hendrik Lenstra Nim multiplication asks : “Prove that $2^{2^i} $ is a primitive root in the field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^{i+1}}} $ if and only if i=0 or 1.”

I’ve struggled with several of the ‘exercises’ in Lenstra’s paper to the extend I feared Alzheimer was setting in, only to find out, after taking pen and paper and spending a considerable amount of time calculating, that they are indeed merely exercises, when looked at properly… (Spoiler-warning : stop reading now if you want to go through this exercise yourself).

In the picture above I’ve added in red the number $x(x+1)=x^2+1 $ to each of the involutions. Clearly, for each pair these numbers are all distinct and we see that for the indicated pairing they make up all numbers strictly less than 8.

By Conway’s simplicity rules (or by checking) the pair (16,17) gives the number 8. In other words, the equation

$x^2+x+8 $ is an irreducible polynomial over $\mathbb{F}_{16} $ having as its roots in $\mathbb{F}_{256} $ the numbers 16 and 17. But then, 16 and 17 are conjugated under the Galois-involution (the Frobenius $y \mapsto y^{16} $). That is, we have $16^{16}=17 $ and $17^{16}=16 $ and hence $16^{17}=8 $. Now, use the multiplication table in $\mathbb{F}_{16} $ given in the previous post (or compute!) to see that 8 is of order 5 (and NOT a generator). As a consequence, the multiplicative order of 16 is 5×17=85 and so 16 cannot be a generator in $\mathbb{F}_{256} $.

For general i one uses the fact that $2^{2^i} $ and $2^{2^i}+1 $ are the roots of the polynomial $x^2+x+\prod_{j<i} 2^{2^j} $ over $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^i}} $ and argues as before.

Right, but then what is the minimal generator satisfying $n^{17}=4 $? By computing we see that the pairings of all numbers in the range 16…31 give us all numbers in the range 8…15 and by the above argument this implies that the 17-th powers of all numbers smaller than 32 must be different from 4. But then, the smallest candidate is 32 and one verifies that indeed $32^{17}=4 $ (use the multiplication table given before).

Hence, we must place Knight $K_{32} $ at root $e^{2 \pi i/255} $ and place the other Knights prior to the 256-th at the corresponding power of 32. I forgot the argument I used to find-by-hand the requested place for Knight 16, but one can verify that $32^{171}=16 $ so we seat $K_{16} $ at root $e^{342 \pi i/255} $.

But what about Knight $K_{256} $? Well, by this time I was quite good at squaring and binary representations of integers, but also rather tired, and decided to leave that task to the computer.

If we denote Nim-addition and multiplication by $\oplus $ and $\otimes $, then Conway’s simplicity results in ONAG establish a field-isomorphism between $~(\mathbb{N},\oplus,\otimes) $ and the field $\mathbb{F}_2(x_0,x_1,x_2,\ldots ) $ where the $x_i $ satisfy the Artin-Schreier equations

$x_i^2+x_i+\prod_{j < i} x_j = 0 $

and the i-th Fermat-field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^i}} $ corresponds to $\mathbb{F}_2(x_0,x_1,\ldots,x_{i-1}) $. The correspondence between numbers and elements from these fields is given by taking $x_i \mapsto 2^{2^i} $. But then, wecan write every 2-power as a product of the $x_i $ and use the binary representation of numbers to perform all Nim-calculations with numbers in these fields.

Therefore, a quick and dirty way (and by no means the most efficient) to do Nim-calculations in the next Fermat-field consisting of all numbers smaller than 65536, is to use sage and set up the field $\mathbb{F}_2(x_0,x_1,x_2,x_3) $ by

R.< x,y,z,t > =GF(2)[] S.< a,b,c,d >=R.quotient((x^2+x+1,y^2+y+x,z^2+z+x*y,t^2+t+x*y*z))

To find the smallest number generating the multiplicative group and satisfying the additional compatibility condition $n^{257}=32 $ we have to find the smallest binary number $i_1i_2 \ldots i_{16} $ (larger than 255) satisfying

(i1*a*b*c*t+i2*b*c*t+i3*a*c*t+i4*c*t+i5*a*b*t+i6*b*t+ i7*a*t+i8*t+i9*a*b*c+i10*b*c+i11*a*c+i12*c+i13*a*b+ i14*b+i15*a+i16)^257=a*c

It takes a 2.4GHz 2Gb-RAM MacBook not that long to decide that the requested generator is 1051 (killing another optimistic conjecture that these generators might be 2-powers). So, we seat Knight

$K_{1051} $ at root $e^{2 \pi i/65535} $ and can then arrange seatings for all Knight queued up until we reach the 65536-th! In particular, the first Knight we couldn’t place before, that is Knight $K_{256} $, will be seated at root $e^{65826 \pi i/65535} $.

If you’re lucky enough to own a computer with more RAM, or have the patience to make the search more efficient and get the seating arrangement for the next Fermat-field, please drop a comment.

I’ll leave you with another Lenstra-exercise which shouldn’t be too difficult for you to solve now : “Prove that $x^3=2^{2^i} $ has three solutions in $\mathbb{N} $ for each $i \geq 2 $.”

Comments closed