Last time we have

Last time we have

seen that the noncommutative manifold of a Riemann surface can be viewed

as that Riemann surface together with a loop in each point. The extra

loop-structure tells us that all finite dimensional representations of

the coordinate ring can be found by separating over points and those

living at just one point are classified by the isoclasses of nilpotent

matrices, that is are parametrized by the partitions (corresponding

to the sizes of the Jordan blocks). In addition, these loops tell us

that the Riemann surface locally looks like a Riemann sphere, so an

equivalent mental picture of the local structure of this

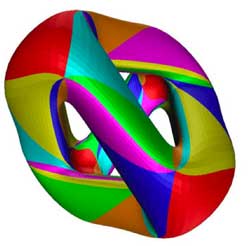

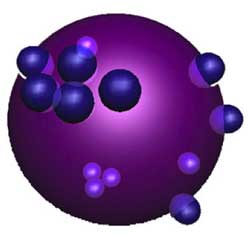

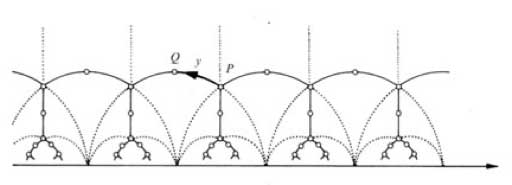

noncommutative manifold is given by the picture on teh left, where the surface is part of the Riemann surface

and a sphere is placed at every point. Today we will consider

genuine noncommutative curves and describe their corresponding

noncommutative manifolds.

Here, a mental picture of such a

Here, a mental picture of such a

_noncommutative sphere_ to keep in mind would be something

like the picture on the right. That is, in most points of the sphere we place as before again

a Riemann sphere but in a finite number of points a different phenomen

occurs : we get a cluster of infinitesimally nearby points. We

will explain this picture with an easy example. Consider the

complex plane $\mathbb{C} $, the points of which are just the

one-dimensional representations of the polynomial algebra in one

variable $\mathbb{C}[z] $ (any algebra map $\mathbb{C}[z] \rightarrow \mathbb{C} $ is fully determined by the image of z). On this plane we

have an automorphism of order two sending a complex number z to its

negative -z (so this automorphism can be seen as a point-reflexion

with center the zero element 0). This automorphism extends to

the polynomial algebra, again induced by sending z to -z. That

is, the image of a polynomial $f(z) \in \mathbb{C}[z] $ under this

automorphism is f(-z).

With this data we can form a noncommutative

algebra, the _skew-group algebra_ $\mathbb{C}[z] \ast C_2 $ the

elements of which are either of the form $f(z) \ast e $ or $g(z) \ast g $ where

$C_2 = \langle g : g^2=e \rangle $ is the cyclic group of order two

generated by the automorphism g and f(z),g(z) are arbitrary

polynomials in z.

The multiplication on this algebra is determined by

the following rules

$(g(z) \ast g)(f(z) \ast e) = g(z)f(-z) \astg $ whereas $(f(z) \ast e)(g(z) \ast g) = f(z)g(z) \ast g $

$(f(z) \ast e)(g(z) \ast e) = f(z)g(z) \ast e $ whereas $(f(z) \ast g)(g(z)\ast g) = f(z)g(-z) \ast e $

That is, multiplication in the

$\mathbb{C}[z] $ factor is the usual multiplication, multiplication in

the $C_2 $ factor is the usual group-multiplication but when we want

to get a polynomial from right to left over a group-element we have to

apply the corresponding automorphism to the polynomial (thats why we

call it a _skew_ group-algebra).

Alternatively, remark that as

a $\mathbb{C} $-algebra the skew-group algebra $\mathbb{C}[z] \ast C_2 $ is

an algebra with unit element 1 = 1\aste and is generated by

the elements $X = z \ast e $ and $Y = 1 \ast g $ and that the defining

relations of the multiplication are

$Y^2 = 1 $ and $Y.X =-X.Y $

hence another description would

be

$\mathbb{C}[z] \ast C_2 = \frac{\mathbb{C} \langle X,Y \rangle}{ (Y^2-1,XY+YX) } $

It can be shown that skew-group

algebras over the coordinate ring of smooth curves are _noncommutative

smooth algebras_ whence there is a noncommutative manifold associated

to them. Recall from last time the noncommutative manifold of a

smooth algebra A is a device to classify all finite dimensional

representations of A upto isomorphism Let us therefore try to

determine some of these representations, starting with the

one-dimensional ones, that is, algebra maps from

$\mathbb{C}[z] \ast C_2 = \frac{\mathbb{C} \langle X,Y \rangle}{ (Y^2-1,XY+YX) } \rightarrow \mathbb{C} $

Such a map is determined by the image of X and that of

Y. Now, as $Y^2=1 $ we have just two choices for the image of Y

namely +1 or -1. But then, as the image is a commutative algebra

and as XY+YX=0 we must have that the image of 2XY is zero whence the

image of X must be zero. That is, we have only

two one-dimensional representations, namely $S_+ : X \rightarrow 0, Y \rightarrow 1 $

and $S_- : X \rightarrow 0, Y \rightarrow -1 $

This is odd! Can

it be that our noncommutative manifold has just 2 points? Of course not.

In fact, these two points are the exceptional ones giving us a cluster

of nearby points (see below) whereas most points of our

noncommutative manifold will correspond to 2-dimensional

representations!

So, let’s hunt them down. The

center of $\mathbb{C}[z]\ast C_2 $ (that is, the elements commuting with

all others) consists of all elements of the form $f(z)\ast e $ with f an

_even_ polynomial, that is, f(z)=f(-z) (because it has to commute

with 1\ast g), so is equal to the subalgebra $\mathbb{C}[z^2]\ast e $.

The

manifold corresponding to this subring is again the complex plane

$\mathbb{C} $ of which the points correspond to all one-dimensional

representations of $\mathbb{C}[z^2]\ast e $ (determined by the image of

$z^2\ast e $).

We will now show that to each point of $\mathbb{C} – { 0 } $

corresponds a simple 2-dimensional representation of

$\mathbb{C}[z]\ast C_2 $.

If a is not zero, we will consider the

quotient of the skew-group algebra modulo the twosided ideal generated

by $z^2\ast e-a $. It turns out

that

$\frac{\mathbb{C}[z]\ast C_2}{(z^2\aste-a)} =

\frac{\mathbb{C}[z]}{(z^2-a)} \ast C_2 = (\frac{\mathbb{C}[z]}{(z-\sqrt{a})}

\oplus \frac{\mathbb{C}[z]}{(z+\sqrt{a})}) \ast C_2 = (\mathbb{C}

\oplus \mathbb{C}) \ast C_2 $

where the skew-group algebra on the

right is given by the automorphism g on $\mathbb{C} \oplus \mathbb{C} $ interchanging the two factors. If you want to

become more familiar with working in skew-group algebras work out the

details of the fact that there is an algebra-isomorphism between

$(\mathbb{C} \oplus \mathbb{C}) \ast C_2 $ and the algebra of $2 \times 2 $ matrices $M_2(\mathbb{C}) $. Here is the

identification

$~(1,0)\aste \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $

$~(0,1)\aste \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $

$~(1,0)\astg \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $

$~(0,1)\astg \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $

so you have to verify that multiplication

on the left hand side (that is in $(\mathbb{C} \oplus \mathbb{C}) \ast

C_2 $) coincides with matrix-multiplication of the associated

matrices.

Okay, this begins to look like what we are after. To

every point of the complex plane minus zero (or to every point of the

Riemann sphere minus the two points ${ 0,\infty } $) we have

associated a two-dimensional simple representation of the skew-group

algebra (btw. simple means that the matrices determined by the images

of X and Y generate the whole matrix-algebra).

In fact, we

now have already classified ‘most’ of the finite dimensional

representations of $\mathbb{C}[z]\ast C_2 $, namely those n-dimensional

representations

$\mathbb{C}[z]\ast C_2 =

\frac{\mathbb{C} \langle X,Y \rangle}{(Y^2-1,XY+YX)} \rightarrow M_n(\mathbb{C}) $

for which the image of X is an invertible $n \times n $ matrix. We can show that such representations only exist when

n is an even number, say n=2m and that any such representation is

again determined by the geometric/combinatorial data we found last time

for a Riemann surface.

That is, It is determined by a finite

number ${ P_1,\dots,P_k } $ of points from $\mathbb{C} – 0 $ where

k is at most m. For each index i we have a positive

number $a_i $ such that $a_1+\dots+a_k=m $ and finally for each i we

also have a partition of $a_i $.

That is our noncommutative

manifold looks like all points of $\mathbb{C}-0 $ with one loop in each

point. However, we have to remember that each point now determines a

simple 2-dimensional representation and that in order to get all

finite dimensional representations with det(X) non-zero we have to

scale up representations of $\mathbb{C}[z^2] $ by a factor two.

The technical term here is that of a Morita equivalence (or that the

noncommutative algebra is an Azumaya algebra over

$\mathbb{C}-0 $).

What about the remaining representations, that

is, those for which Det(X)=0? We have already seen that there are two

1-dimensional representations $S_+ $ and $S_- $ lying over 0, so how

do they fit in our noncommutative manifold? Should we consider them as

two points and draw also a loop in each of them or do we have to do

something different? Rememer that drawing a loop means in our

geometry -> representation dictionary that the representations

living at that point are classified in the same way as nilpotent

matrices.

Hence, drawing a loop in $S_+ $ would mean that we have a

2-dimensional representation of $\mathbb{C}[z]\ast C_2 $ (different from

$S_+ \oplus S_+ $) and any such representation must correspond to

matrices

$X \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $ and $Y \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $

But this is not possible as these matrices do

_not_ satisfy the relation XY+YX=0. Hence, there is no loop in $S_+ $

and similarly also no loop in $S_- $.

However, there are non

semi-simple two dimensional representations build out of the simples

$S_+ $ and $S_- $. For, consider the matrices

$X \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $ and $Y \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix} $

then these

matrices _do_ satisfy XY+YX=0! (and there is another matrix-pair

interchanging $\pm 1 $ in the Y-matrix). In erudite terminology this

says that there is a _nontrivial extension_ between $S_+ $ and $S_- $

and one between $S_- $ and $S_+ $.

In our dictionary we will encode this

information by the picture

$\xymatrix{\vtx{}

\ar@/^2ex/[rr] & & \vtx{} \ar@/^2ex/[ll]} $

where the two

vertices correspond to the points $S_+ $ and $S_- $ and the arrows

represent the observed extensions. In fact, this data suffices to finish

our classification project of finite dimensional representations of

the noncommutative curve $\mathbb{C}[z] \ast C_2 $.

Those with Det(X)=0

are of the form : $R \oplus T $ where R is a representation with

invertible X-matrix (which we classified before) and T is a direct

sum of representations involving only the simple factors $S_+ $ and

$S_- $ and obtained by iterating the 2-dimensional idea. That is, for

each factor the Y-matrix has alternating $\pm 1 $ along the diagonal

and the X-matrix is the full nilpotent Jordan-matrix.

So

here is our picture of the noncommutative manifold of the

noncommutative curve $\mathbb{C}[z]\ast C_2 $ : the points are all points

of $\mathbb{C}-0 $ together with one loop in each of them together

with two points lying over 0 where we draw the above picture of arrows

between them. One should view these two points as lying

infinetesimally close to each other and the gluing

data

$\xymatrix{\vtx{} \ar@/^2ex/[rr] & & \vtx{}

\ar@/^2ex/[ll]} $

contains enough information to determine

that all other points of the noncommutative manifold in the vicinity of

this cluster should be two dimensional simples! The methods used

in this simple minded example are strong enough to determine the

structure of the noncommutative manifold of _any_ noncommutative curve.

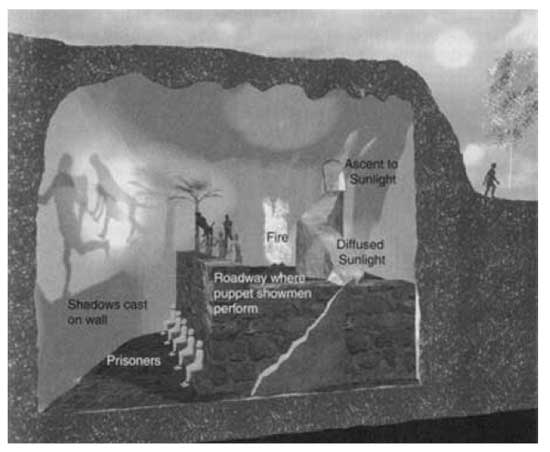

So, let us look at a real-life example. Once again, take the

Kleinian quartic In a previous

course-post we recalled that

there is an action by automorphisms on the Klein quartic K by the

finite simple group $PSL_2(\mathbb{F}_7) $ of order 168. Hence, we

can form the noncommutative Klein-quartic $K \ast PSL_2(\mathbb{F}_7) $

(take affine pieces consisting of complements of orbits and do the

skew-group algebra construction on them and then glue these pieces

together again).

We have also seen that the orbits are classified

under a Belyi-map $K \rightarrow \mathbb{P}^1_{\mathbb{C}} $ and that this map

had the property that over any point of $\mathbb{P}^1_{\mathbb{C}}

– { 0,1,\infty } $ there is an orbit consisting of 168 points

whereas over 0 (resp. 1 and $\infty $) there is an orbit

consisting of 56 (resp. 84 and 24 points).

So what is

the noncommutative manifold associated to the noncommutative Kleinian?

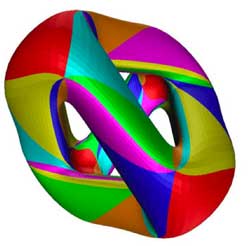

Well, it looks like the picture we had at the start of this

post  For all but three points of the Riemann sphere

For all but three points of the Riemann sphere

$\mathbb{P}^1 – { 0,1,\infty } $ we have one point and one loop

(corresponding to a simple 168-dimensional representation of $K \ast

PSL_2(\mathbb{F}_7) $) together with clusters of infinitesimally nearby

points lying over 0,1 and $\infty $ (the cluster over 0

is depicted, the two others only indicated).

Over 0 we have

three points connected by the diagram

$\xymatrix{& \vtx{} \ar[ddl] & \\ & & \\ \vtx{} \ar[rr] & & \vtx{} \ar[uul]} $

where each of the vertices corresponds to a

simple 56-dimensional representation. Over 1 we have a cluster of

two points corresponding to 84-dimensional simples and connected by

the picture we had in the $\mathbb{C}[z]\ast C_2 $ example).

Finally,

over $\infty $ we have the most interesting cluster, consisting of the

seven dwarfs (each corresponding to a simple representation of dimension

24) and connected to each other via the

picture

$\xymatrix{& & \vtx{} \ar[dll] & & \\ \vtx{} \ar[d] & & & & \vtx{} \ar[ull] \\ \vtx{} \ar[dr] & & & & \vtx{} \ar[u] \\ & \vtx{} \ar[rr] & & \vtx{} \ar[ur] &} $

Again, this noncommutative manifold gives us

all information needed to give a complete classification of all finite

dimensional $K \ast PSL_2(\mathbb{F}_7) $-representations. One

can prove that all exceptional clusters of points for a noncommutative

curve are connected by a cyclic quiver as the ones above. However, these

examples are still pretty tame (in more than one sense) as these

noncommutative algebras are finite over their centers, are Noetherian

etc. The situation will become a lot wilder when we come to exotic

situations such as the noncommutative manifold of

$SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $…

Here, a mental picture of such a

Here, a mental picture of such a