An integral $n$-dimensional lattice $L$ is the set of all integral linear combinations

\[

L = \mathbb{Z} \lambda_1 \oplus \dots \oplus \mathbb{Z} \lambda_n \]

of base vectors $\{ \lambda_1,\dots,\lambda_n \}$ of $\mathbb{R}^n$, equipped with the usual (positive definite) inner product, satisfying

\[

(\lambda, \mu ) \in \mathbb{Z} \quad \text{for all $\lambda,\mu \in \mathbb{Z}$.} \]

But then, $L$ is contained in its dual lattice $L^* = Hom_{\mathbb{Z}}(L,\mathbb{Z})$, and if $L = L^*$ we say that $L$ is unimodular.

If all $(\lambda,\lambda) \in 2 \mathbb{Z}$, we say that $L$ is an even lattice. Even unimodular lattices (such as the $E_8$-lattice or the $24$ Niemeier lattices) are wonderful objects, but they can only live in dimensions $n$ which are multiples of $8$.

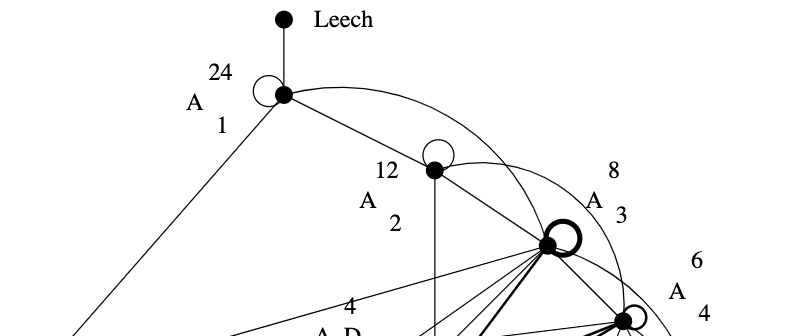

Just like the Conway group $Co_0 = .0$ is the group of rotations of the Leech lattice $\Lambda$, one might ask whether there is a very special lattice on which the Monster group $\mathbb{M}$ acts faithfully by rotations. If such a lattice exists, it must live in dimension at least $196883$.

Simon Norton (1952-2019) – Photo Credit

A first hint of such a lattice is in Conway’s original paper A simple construction for the Fischer-Griess monster group (but not in the corresponding chapter 29 of SPLAG).

Conway writes that Simon Norton showed ‘by a very simple computations that does not even require knowledge of the conjugacy classes, that any $198883$-dimensional representation of the Monster must support an invariant algebra’, which, after adding an identity element $1$, we now know as the $196884$-dimensional Griess algebra.

Further, on page 529, Conway writes:

Norton has shown that the lattice $L$ spanned by vectors of the form $1,t,t \ast t’$, where $t$ and $t’$ are transposition vectors, is closed under the algebra multiplication and integral with respect to the doubled inner product $2(u,v)$. The dual quotient $L^*/L$ is cyclic of order some power of $4$, and we believe that in fact $L$ is unimodular.

Here, transposition vectors correspond to transpositions in $\mathbb{M}$, that is, elements of conjugacy class $2A$.

I only learned about this lattice yesterday via the MathOverflow-post A lattice with Monster group symmetries by Adam P. Goucher.

In his post, Adam considers the $196883$-dimensional lattice $L’ = L \cap 1^{\perp}$ (which has $\mathbb{M}$ as its rotation symmetry group), and asks for the minimal norm (squared) of a lattice point, which he believes is $448$, and for the number of minimal vectors in the lattice, which might be

\[

2639459181687194563957260000000 = 9723946114200918600 \times 27143910000 \]

the number of oriented arcs in the Monster graph.

Here, the Monster graph has as its vertices the elements of $\mathbb{M}$ in conjugacy class $2A$ (which has $9723946114200918600$ elements) and with an edge between two vertices if their product in $\mathbb{M}$ again belongs to class $2A$, so the valency of the graph must be $27143910000$, as explained in that old post the monster graph and McKay’s observation.

When I asked Adam whether he had more information about his lattice, he kindly informed me that Borcherds told him that the Norton lattice $L$ didn’t turn out to be unimodular after all, but that a unimodular lattice with monstrous symmetry had been constructed by Scott Carnahan in the paper A Self-Dual Integral Form of the Moonshine Module.

Scott Carnahan – Photo Credit

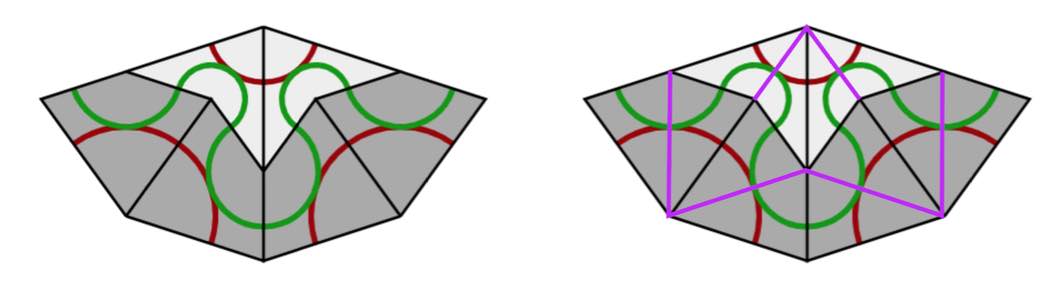

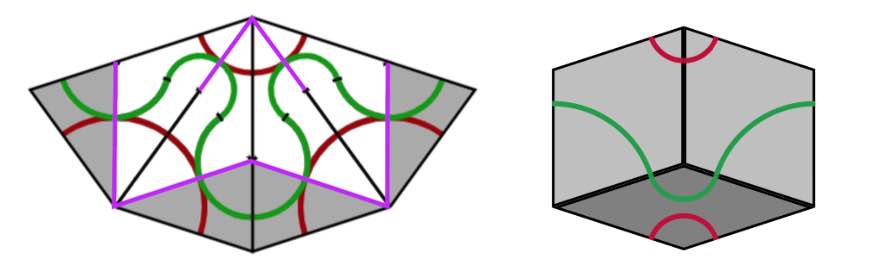

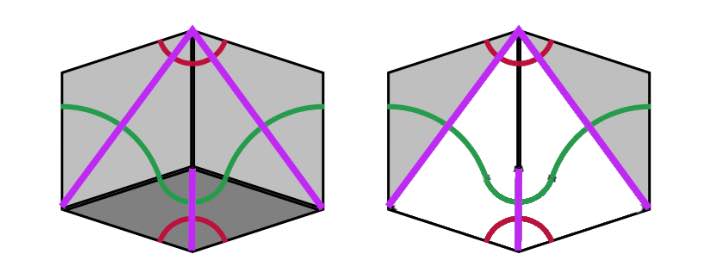

The major steps (or better, the little bit of it I could grasp in this short time) in the construction of this unimodular $196884$-dimensional monstrous lattice might put a smile on your face if you are an affine scheme aficionado.

Already in his paper Vertex algebras, Kac-Moody algebras, and the Monster, Richard Borcherds described an integral form of any lattice vertex algebra. We’ll be interested in the lattice vertex algebra $V_{\Lambda}$ constructed from the Leech lattice $\Lambda$ and call its integral form $(V_{\Lambda})_{\mathbb{Z}}$.

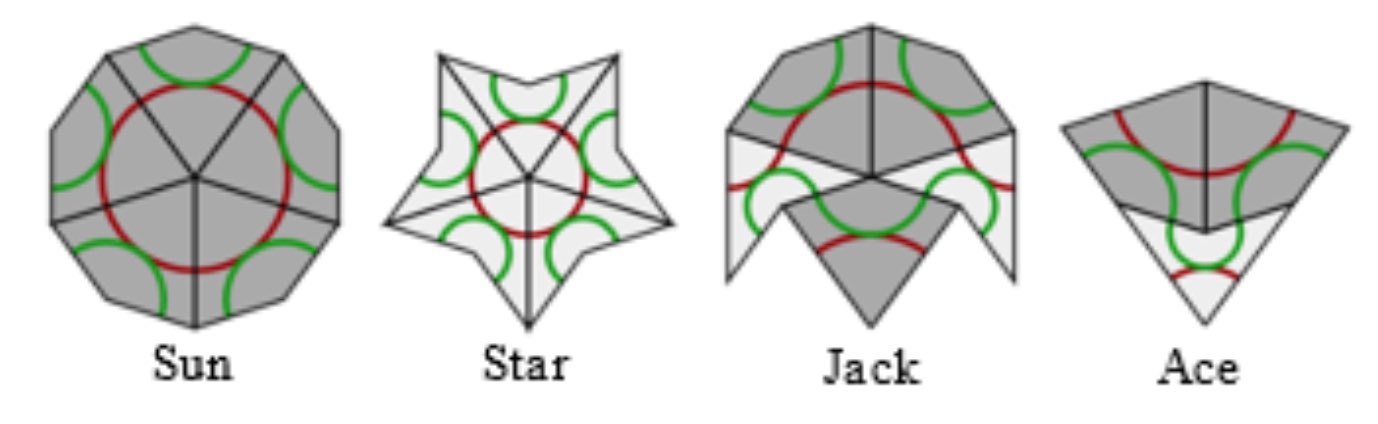

One constructs the Moonshine module $V^{\sharp}$ from $V_{\Lambda}$ by a process called ‘cyclic orbifolding’, a generalisation of the original construction by Frenkel, Lepowsky and Meurman. In fact, there are now no less than 51 constructions of the moonshine module.

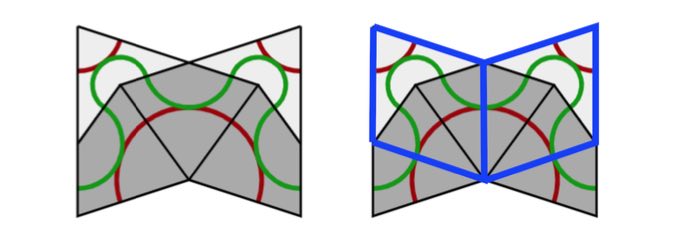

One starts with a fixed point free rotation $r_p$ of $\Lambda$ in $Co_0$ of prime order $p \in \{ 2,3,5,7,13 \}$, which one can lift to an automorphism $g_p$ of the vertex algebra $V_{\Lambda}$ of order $p$ giving an isomorphism $V_{\Lambda}/g_p \simeq V^{\sharp}$ of vertex operator algebras over $\mathbb{C}$.

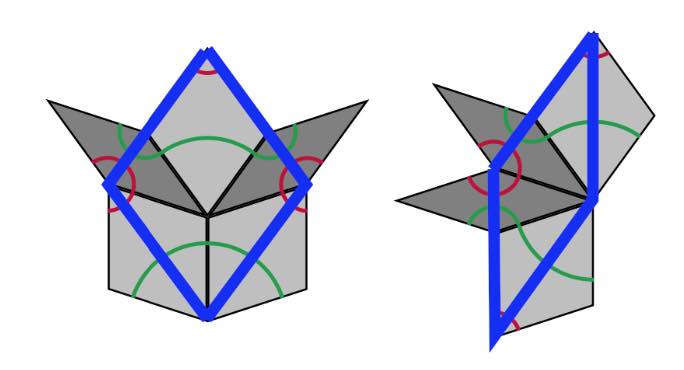

For two distinct primes $p,p’ \in \{ 2,3,5,7,13 \}$ if $Co_0$ has an element of order $p.p’$ one can find one such $r_{pp’}$ such that $r_{pp’}^p=r_{p’}$ and $r_{pp’}^{p’}=r_p$, and one can lift $r_{pp’}$ to an automorphism $g_{pp’}$ of $V_{\Lambda}$ such that $V_{\Lambda}/g_{pp’} \simeq V_{\Lambda}$ as vertex operator algebras over $\mathbb{C}$.

Problem is that these lifts of automorphisms and the isomorphisms are not compatible with the integral form $(V_{\Lambda})_{\mathbb{Z}}$ of $V_{\Lambda}$, but ‘essentially’, they can be performed on

\[

(V_{\Lambda})_{\mathbb{Z}} \otimes_{\mathbb{Z}} \mathbb{Z}[\frac{1}{pp’},\zeta_{2pp’}] \]

where $\zeta_{2pp’}$ is a primitive $2pp’$-th root of unity. These then give a $\mathbb{Z}[\tfrac{1}{pp’},\zeta_{2pp’}]$-form on $V^{\sharp}$.

Next, one uses a lot of subgroup information about $\mathbb{M}$ to prove that these $\mathbb{Z}[\tfrac{1}{pp’},\zeta_{2pp’}]$-forms of $V^{\sharp}$ have $\mathbb{M}$ as their automorphism group.

Then, using all his for different triples in $\{ 2,3,5,7,13 \}$ one can glue and use faithfully flat descent to get an integral form $V^{\sharp}_{\mathbb{Z}}$ of the moonshine module with monstrous symmetry and such that the inner product on $V^{\sharp}_{\mathbb{Z}}$ is positive definite.

Finally, one looks at the weight $2$ subspace of $V^{\sharp}_{\mathbb{Z}}$ which gives us our Carnahan’s $196884$-dimensional unimodular lattice with monstrous symmetry!

Beautiful as this is, I guess it will be a heck of a project to deduce even the simplest of facts about this wonderful lattice from running through this construction.

For example, what is the minimal length of vectors? What is the number of minimal length vectors? And so on. All info you might have is very welcome.

One Comment