One of the few certainties we have on the Bourbaki-Petard wedding invitation is that it was printed in, and distributed out of Cambridge in the spring of 1939, presumably around mid April.

So, what was going on, mathematically, in and around Trinity and St. John’s College, at that time?

Well, there was the birth of Eureka, the journal of the Archimedeans, the mathematical society of the University of Cambridge. Eureka is one of the oldest recreational mathematics publications still in existence.

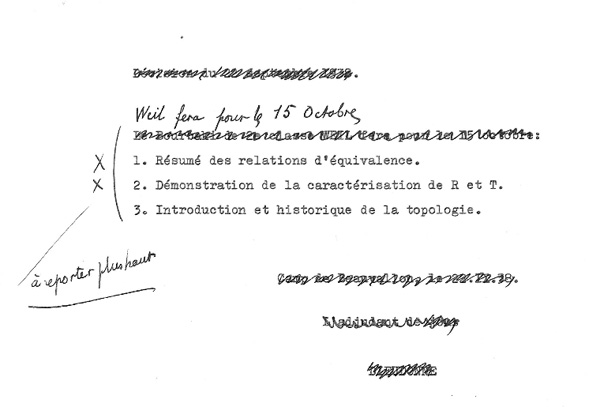

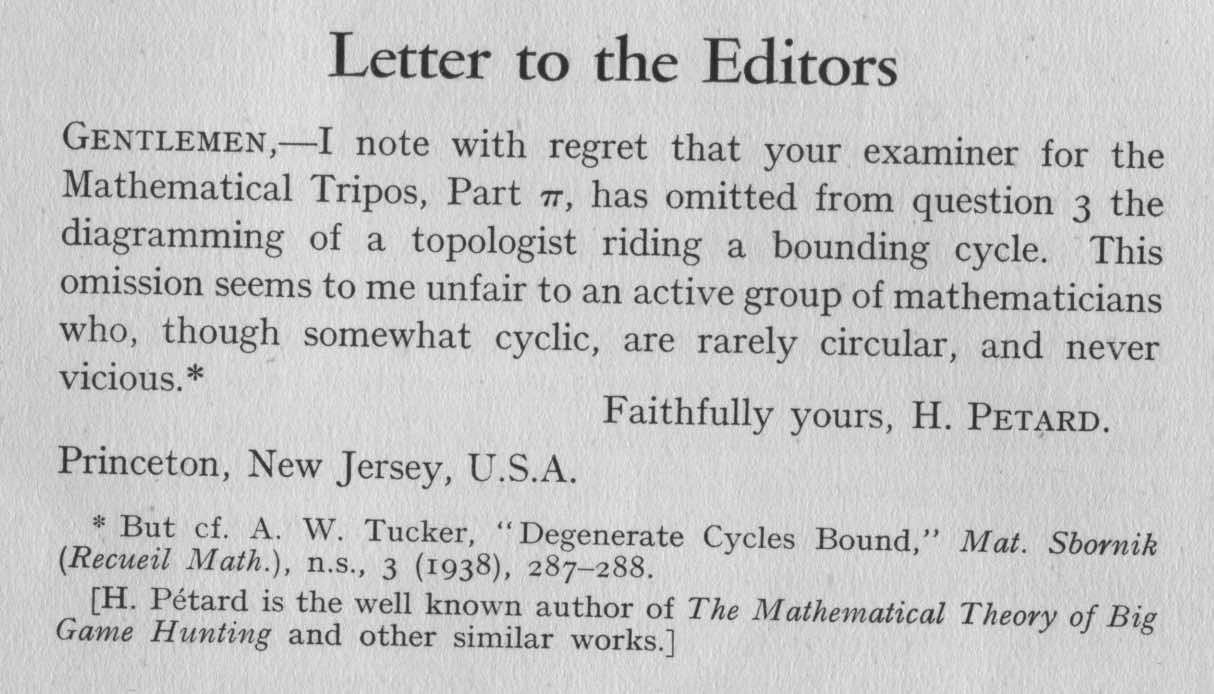

Since last year the back issues of Eureka are freely available online, unfortunately missing out the very first two numbers from 1939. Ralph Boas, one of the wedding-conspirators, was among the first to contribute to Eureka. In the second number, in may 1939, he wrote an article on “Undergraduate mathematics in America”. And, in may 1940 (number 4 of Eureka) even the lion hunter H. Petard wrote a short ‘Letter to the editors’.

But, no doubt the hottest thing that spring in Cambridge were Ludwig Wittgenstein’s ‘Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics’. Wittgenstein was just promoted to Professor after G.E. Moore resigned the chair in philosophy.

For several terms at Cambridge in 1939, Ludwig Wittgenstein lectured on the philosophical foundations of mathematics. A lecture class taught by Wittgenstein, however, hardly resembled a lecture. He sat on a chair in the middle of the room, with some of the class sitting in chairs, some on the floor. He never used notes. He paused frequently, sometimes for several minutes, while he puzzled out a problem. He often asked his listeners questions and reacted to their replies. Many meetings were largely conversation.

These lectures were attended by, among others, D. A. T. Gasking, J. N. Findlay, Stephen Toulmin, Alan Turing, G. H. von Wright, R. G. Bosanquet, Norman Malcolm, Rush Rhees, and Yorick Smythies.

Here’s a clip from the film Wittgenstein, directed by Derek Jarman.

Missing from the list of people attending Wittgenstein’s lectures is Andre Weil, a Bourbaki member and the principal author of the wedding invitation.

Weil was in Cambridge in the spring of 1939 on a travel grant from the French research organisation for visits to the UK and Northern Europe. At that time, Weil held a position at the University of Strasbourg, uncomfortably close to Nazi-Germany.

Weil not attending Wittgenstein’s lectures is strange for several reasons. Weil was then correcting the galley proofs of Bourbaki’s first ever booklet, their own treatment of set theory, which appeared in 1939.

But also on a personal level, Andre Weil must have been intrigued by Wittgenstein’s philosophy, as it was close to that of his own sister Simone Weil

There are many parallels between the thinkers Simone Weil and Ludwig Wittgenstein. They each lived in a tense relationship with religion, with both being estranged from their cultural Jewish ancestry, and both being tempted at various times by the teachings of Catholicism.

They both underwent a profound and transformative mystical turn early into their careers. Both operated against the backdrop of escalating global conflict in the early 20th century.

Both were concerned, amongst other things, with questions of culture, ethics, aesthetics, epistemology, science, and necessity. And, perhaps most notably, they both sought to radically embody their ideas and physically ‘live’ their philosophies.

Andre and Simone Weil in Knokke-Zoute, 1922 – Photo Credit

Another reason why Weil might have been interested to hear Wittgenstein on the foundations of mathematics was a debate held in Paris of few months previously.

On February 4th 1939, the French Society of Philosophy invited Albert Lautman and Jean Cavaillès ‘to define what constitutes the ‘life of mathematics’, between historical contingency and internal necessity, describe their respective projects, which attempt to think mathematics as an experimental science and as an ideal dialectics, and respond to interventions from some eminent mathematicians and philosophers.’

Among the mathematicians present and contributing to the discussion were Weil’s brothers in arms, Henri Cartan, Charles Ehresmann, and Claude Chabauty.

As Chabauty left soon afterwards to study with Mordell in Manchester, and visited Weil in Cambridge, Andre Weil must have known about this discussion.

The record of this February 4th meeting is available here (in French), and in English translation from here.

Jean Cavaillès took part in the French resistance, was arrested and shot by the Nazis on April 4th 1944. Albert Lautman was shot by the Nazis in Toulouse on 1 August 1944.

Jean Cavailles (2nd on the right) 1903-1944 – Photo Credit

A book review of Wittgenstein’s Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics by G. Kreisel is available from the Bulletin of the AMS. Curiously, Kreisel compares Wittgenstein’s approach to … Bourbaki’s very own manifesto L’architecture des mathématiques.

For all these reasons it is strange that Andre Weil apparently didn’t show much interest in Wittgenstein’s lectures.

Had he more urgent things on his mind, like prepping for a wedding?

Comments closed First, the few facts we know about this Bourbaki congress, mostly from

First, the few facts we know about this Bourbaki congress, mostly from