After a lengthy spring-break, let us continue with our course on noncommutative geometry and $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $-representations. Last time, we have explained Grothendiecks mantra that all algebraic curves defined over number fields are contained in the profinite compactification

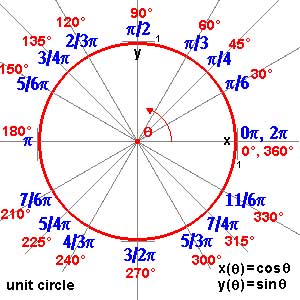

$\widehat{SL_2(\mathbb{Z})} = \underset{\leftarrow}{lim}~SL_2(\mathbb{Z})/N $ of the modular group $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ and in the knowledge of a certain subgroup G of its group of outer automorphisms. In particular we have seen that many curves defined over the algebraic numbers $\overline{\mathbb{Q}} $ correspond to permutation representations of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $. The profinite compactification $\widehat{SL_2}=\widehat{SL_2(\mathbb{Z})} $ is a continuous group, so it makes sense to consider its continuous n-dimensional representations $\mathbf{rep}_n^c~\widehat{SL_2} $ Such representations are known to have a finite image in $GL_n(\mathbb{C}) $ and therefore we get an embedding $\mathbf{rep}_n^c~\widehat{SL_2} \hookrightarrow \mathbf{rep}_n^{ss}~SL_n(\mathbb{C}) $ into all n-dimensional (semi-simple) representations of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $. We consider such semi-simple points as classical objects as they are determined by – curves defined over $\overline{Q} $ – representations of (sporadic) finite groups – modlart data of fusion rings in RCTF – etc… To get a feel for the distinction between these continuous representations of the cofinite completion and all representations, consider the case of $\hat{\mathbb{Z}} = \underset{\leftarrow}{lim}~\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z} $. Its one-dimensional continuous representations are determined by roots of unity, whereas all one-dimensional (necessarily simple) representations of $\mathbb{Z}=C_{\infty} $ are determined by all elements of $\mathbb{C} $. Hence, the image of $\mathbf{rep}_1^c~\hat{\mathbb{Z}} \hookrightarrow \mathbf{rep}_1~C_{\infty} $ is contained in the unit circle

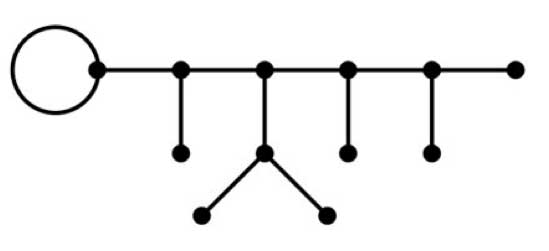

and though these points are very special there are enough of them (technically, they form a Zariski dense subset of all representations). Our aim will be twofold : (1) when viewing a classical object as a representation of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ we can define its modular content (which will be the noncommutative tangent space in this classical point to the noncommutative manifold of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $). In this way we will associate noncommutative gadgets to our classical object (such as orders in central simple algebras, infinite dimensional Lie algebras, noncommutative potentials etc. etc.) which give us new tools to study these objects. (2) conversely, as we control the tangentspaces in these special points, they will allow us to determine other $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $-representations and as we vary over all classical objects, we hope to get ALL finite dimensional modular representations. I agree this may all sound rather vague, so let me give one example we will work out in full detail later on. Remember that one can reconstruct the sporadic simple Mathieu group $M_{24} $ from the dessin d’enfant

- This

- dessin determines a 24-dimensional permutation representation (of

- $M_{24} $ as well of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $) which

- decomposes as the direct sum of the trivial representation and a simple

- 23-dimensional representation. We will see that the noncommutative

- tangent space in a semi-simple representation of

- $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ is determined by a quiver (that is, an

- oriented graph) on as many vertices as there are non-isomorphic simple

- components. In this special case we get the quiver on two points

- $\xymatrix{\vtx{} \ar@/^2ex/[rr] & & \vtx{} \ar@/^2ex/[ll]

- \ar@{=>}@(ur,dr)^{96} } $ with just one arrow in each direction

- between the vertices and 96 loops in the second vertex. To the

- experienced tangent space-reader this picture (and in particular that

- there is a unique cycle between the two vertices) tells the remarkable

- fact that there is **a distinguished one-parameter family of

- 24-dimensional simple modular representations degenerating to the

- permutation representation of the largest Mathieu-group**. Phrased

- differently, there is a specific noncommutative modular Riemann surface

- associated to $M_{24} $, which is a new object (at least as far

- as I’m aware) associated to this most remarkable of sporadic groups.

- Conversely, from the matrix-representation of the 24-dimensional

- permutation representation of $M_{24} $ we obtain representants

- of all of this one-parameter family of simple

- $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $-representations to which we can then perform

- noncommutative flow-tricks to get a Zariski dense set of all

- 24-dimensional simples lying in the same component. (Btw. there are

- also such noncommutative Riemann surfaces associated to the other

- sporadic Mathieu groups, though not to the other sporadics…) So this

- is what we will be doing in the upcoming posts (10) : explain what a

- noncommutative tangent space is and what it has to do with quivers (11)

- what is the noncommutative manifold of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $? and what is its connection with the Kontsevich-Soibelman coalgebra? (12)

- is there a noncommutative compactification of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $? (and other arithmetical groups) (13) : how does one calculate the noncommutative curves associated to the Mathieu groups? (14) : whatever comes next… (if anything).

Comments