A projective plane of order $n$ is a collection of $n^2+n+1$ lines and $n^2+n+1$ points satisfying:

- every line contains exactly $n+1$ points

- every point lies on exactly $n+1$ lines

- any two distinct lines meet at exactly one point

- any two distinct points lie on exactly one line

Clearly, if $q=p^k$ is a pure prime power, then the projective plane over $\mathbb{F}_q$, $\mathbb{P}^2(\mathbb{F}_q)$ (that is, all nonzero triples of elements from the finite field $\mathbb{F}_q$ up to simultaneous multiplication with a non-zero element from $\mathbb{F}_q$) is a projective plane of order $q$.

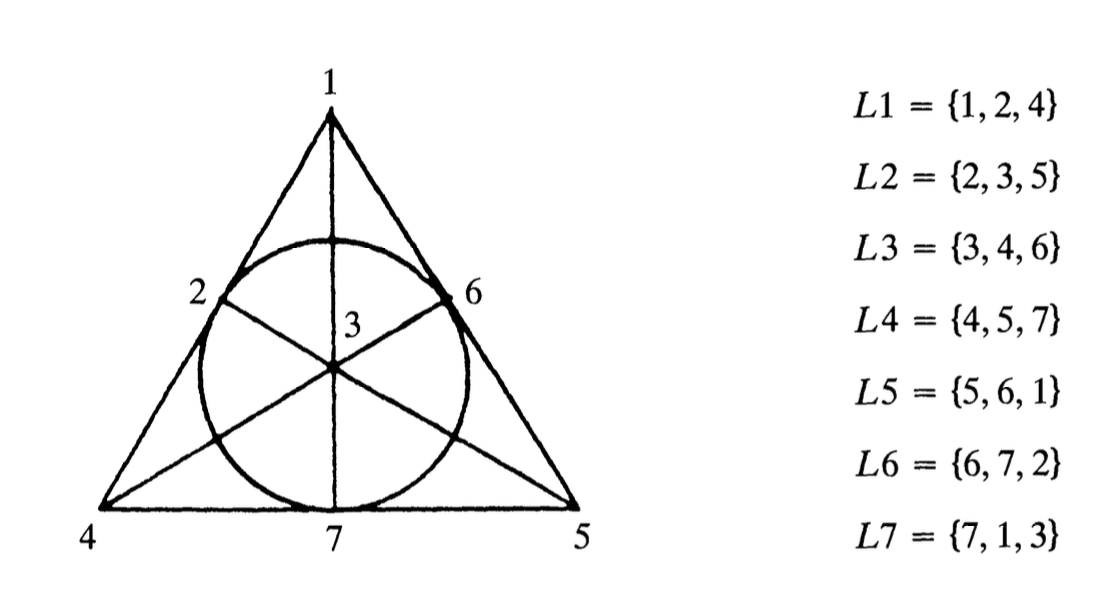

The easiest example being $\mathbb{P}^2(\mathbb{F}_2)$ consisting of seven points and lines

But, there are others. A triangle is a projective plane of order $1$, which is not of the above form, unless you believe in the field with one element $\mathbb{F}_1$…

And, apart from $\mathbb{P}^2(\mathbb{F}_{3^2})$, there are three other, non-isomorphic, projective planes of order $9$.

It is clear then that for all $n < 10$, except perhaps $n=6$, a projective plane of order $n$ exists.

In 1938, Raj Chandra Bose showed that there is no plane of order $6$ as there cannot be $5$ mutually orthogonal Latin squares of order $6$, when even the problem of two orthogonal squares of order $6$ (see Euler’s problem of the $36$ officers) is impossible.

Yeah yeah Bob, I know it has a quantum solution.

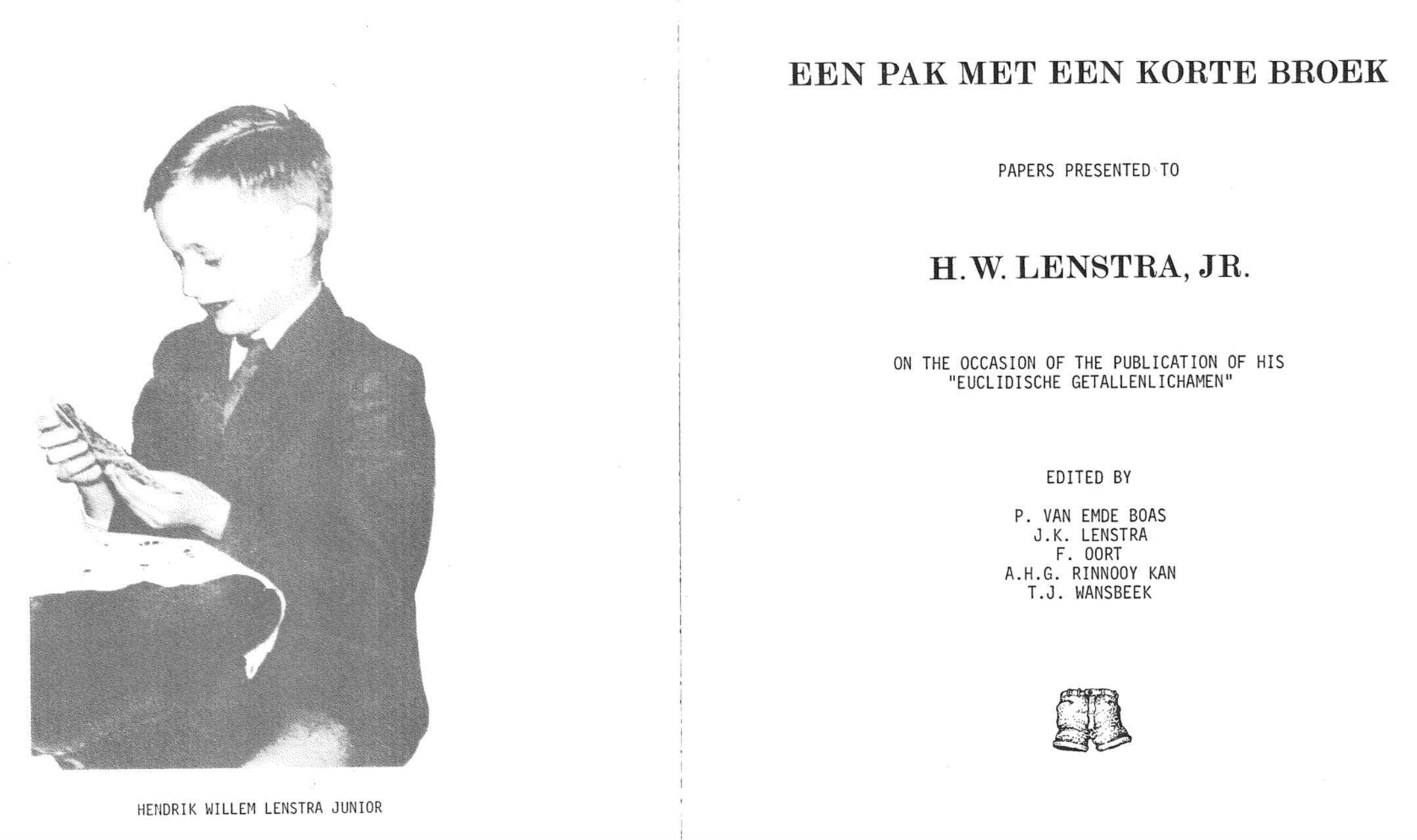

Anyway by May 1977, when Lenstra’s Festschrift ‘Een pak met een korte broek’ (a suit with shorts) was published, the existence of a projective plane of order $10$ was still wide open.

That’s when Andrew Odlyzko (probably known best for his numerical work on the Riemann zeta function) and Neil Sloane (probably best known as the creator of the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences) joined forces to publish in Lenstra’s festschrift a note claiming (jokingly) the existence of a projective plane of order ten, as they were able to find a finite field of ten elements.

Here’s a transcript:

A PROJECTIVE PLAIN OF ORDER TEN

A. M. Odlyzko and N.J.A. Sloane

This note settles in the affirmative the notorious question of the existence of a projective plain of order ten.

It is well-known that if a finite field $F$ is given containing $n$ elements, then the projective plain of order $n$ can be immediately constructed (see M. Hall Jr., Combinatorial Theory, Blaisdell, Waltham, Mass. 1967 and D.R. Hughes and F.C. Piper, Projective Planes, Springer-Verlag, N.Y., 1970).

For example, the points of the plane are represented by the nonzero triples $(\alpha,\beta,\gamma)$ of elements of $F$, with the convention that $(\alpha,\beta,\gamma)$ and $(r\alpha, r\beta, r\gamma)$ represent the same point, for all nonzero $r \in F$.

Furthermore this plain even has the desirable property that Desargues’ theorem holds there.

What makes this note possible is our recent discovery of a field containing exactly ten elements: we call it the digital field.

We first show that this field exists, and then give a childishly simple construction which the reader can easily verify.

The Existence Proof

Since every real number can be written in the decimal system we conclude that

\[

\mathbb{R} = GF(10^{\omega}) \]

Now $\omega = 1.\omega$, so $1$ divides $\omega$. Therefore by a standard theorem from field theory (e.g. B. L. van der Waerden, Modern Algebra, Ungar, N.Y., 1953, 2nd edition, Volume 1, p. 117) $\mathbb{R}$ contains a subfield $GF(10)$. This completes the proof.

The Construction

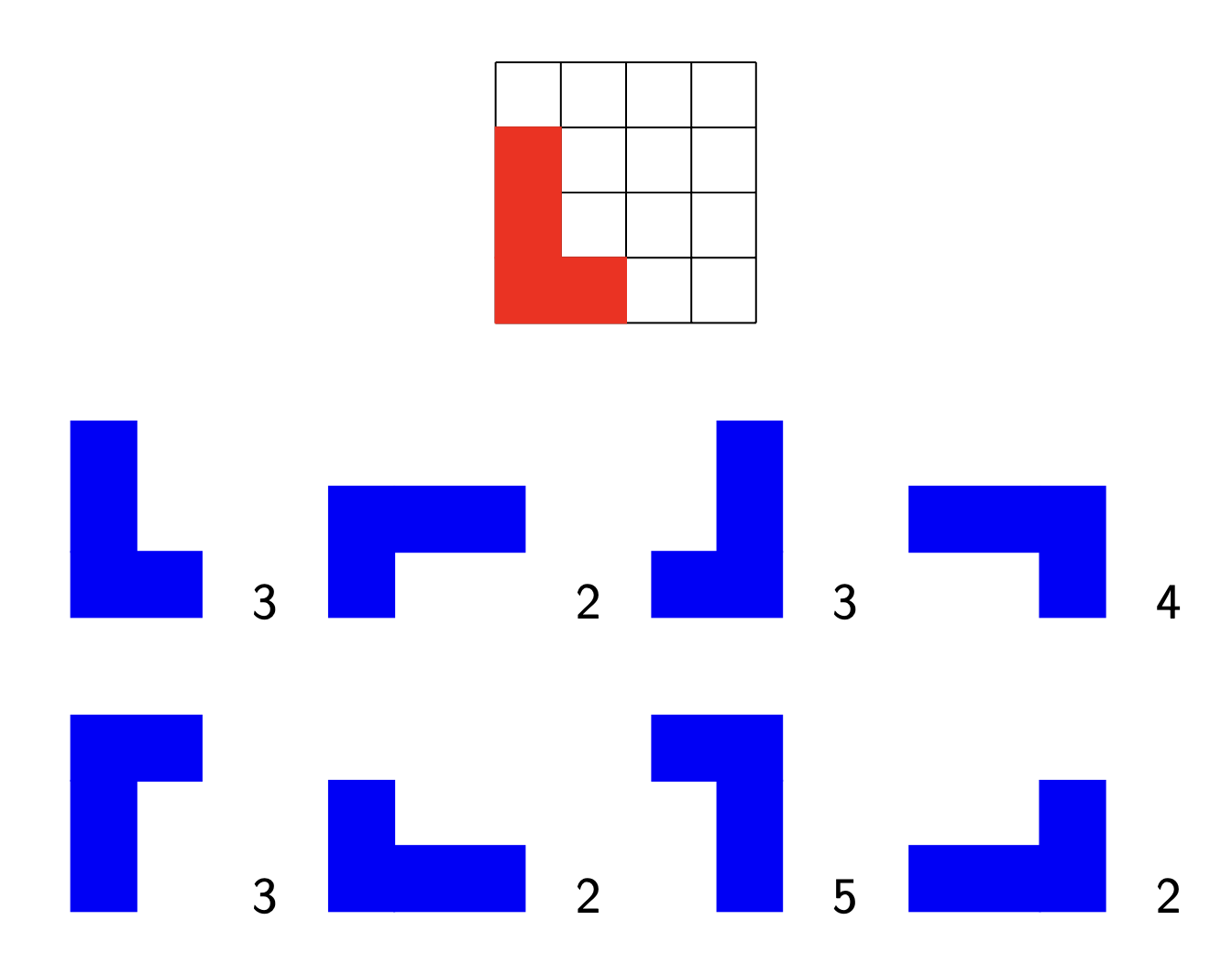

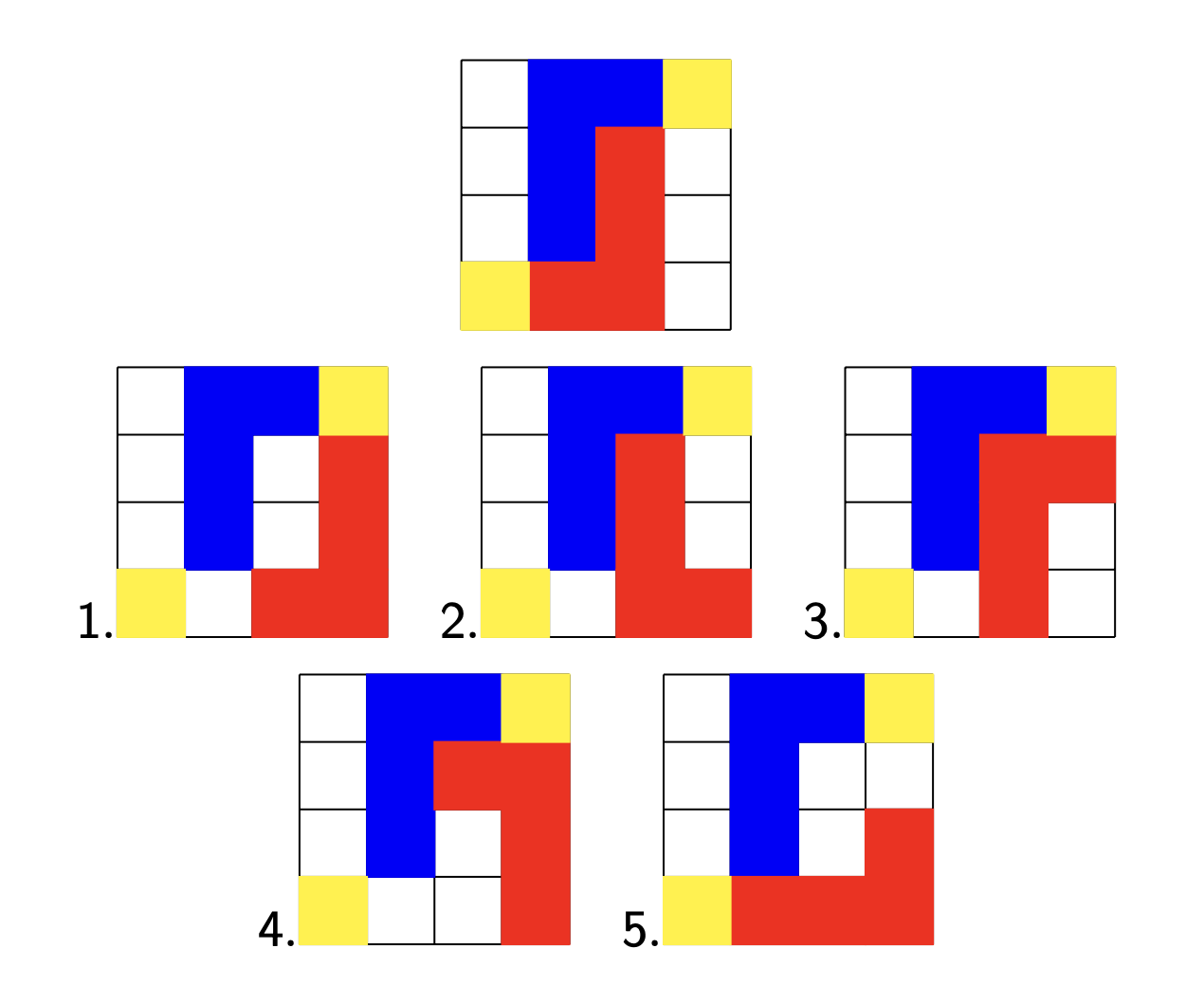

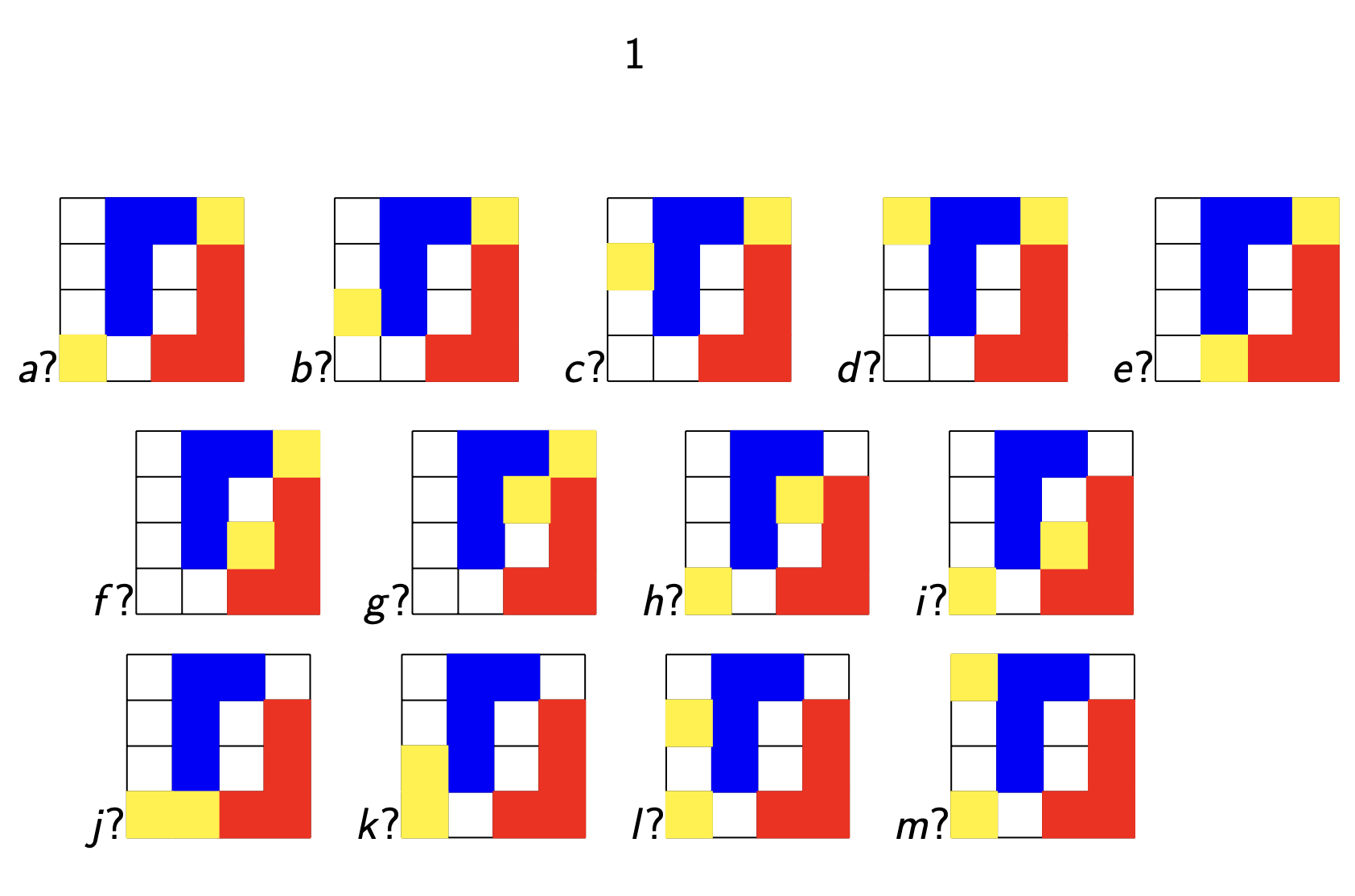

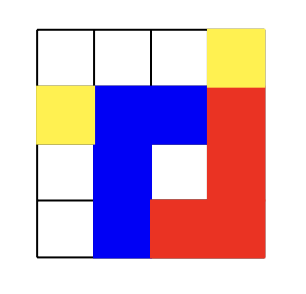

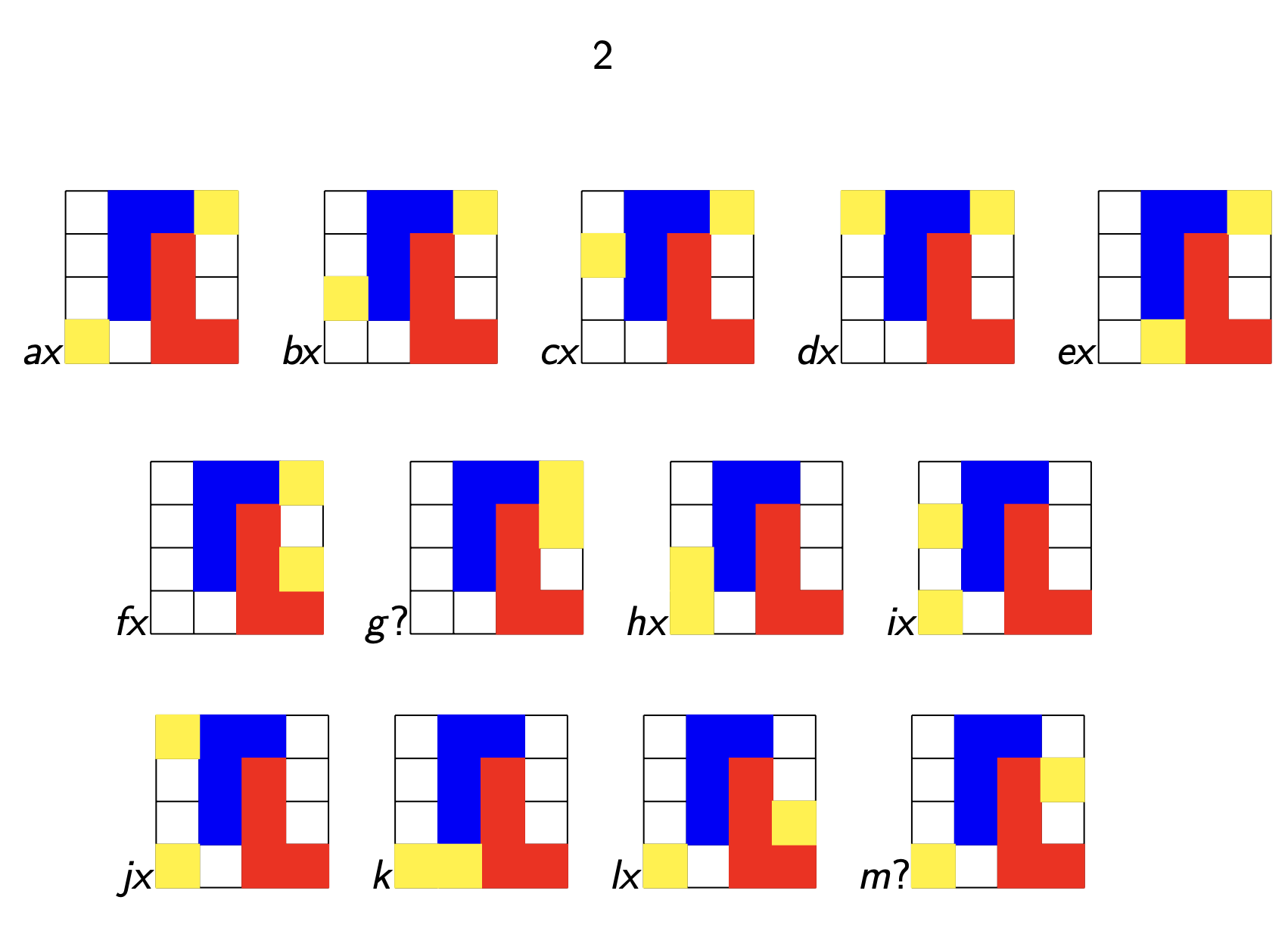

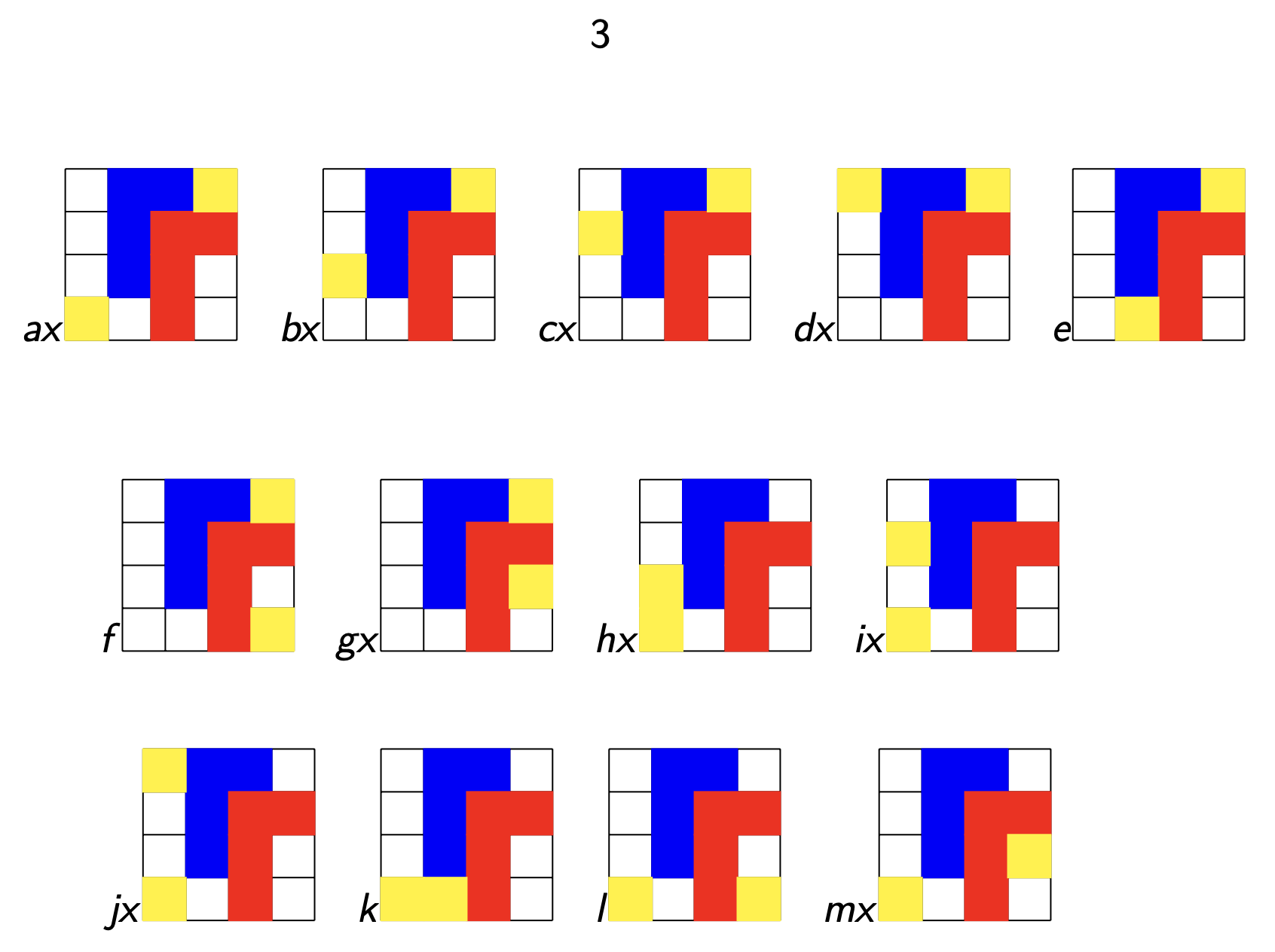

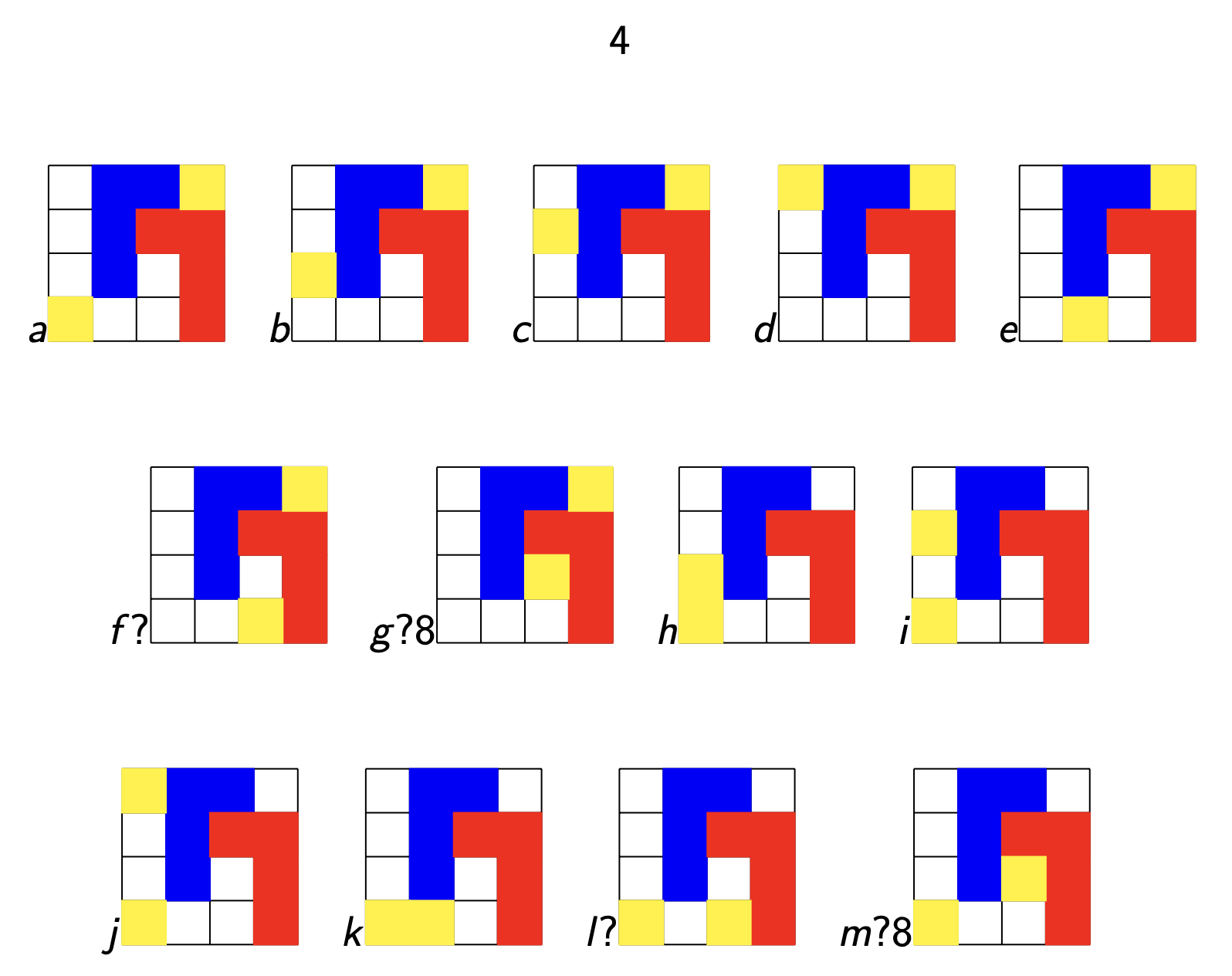

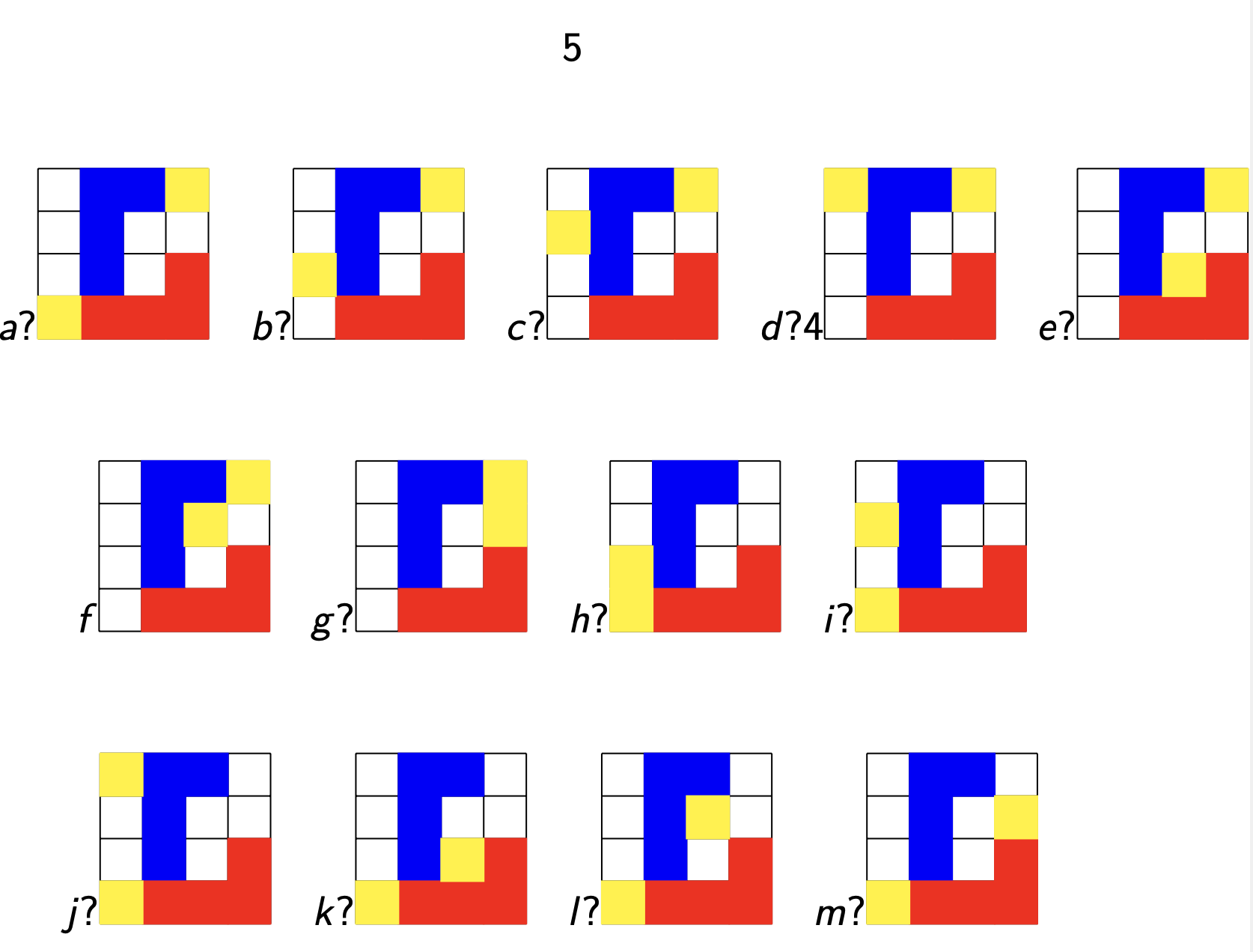

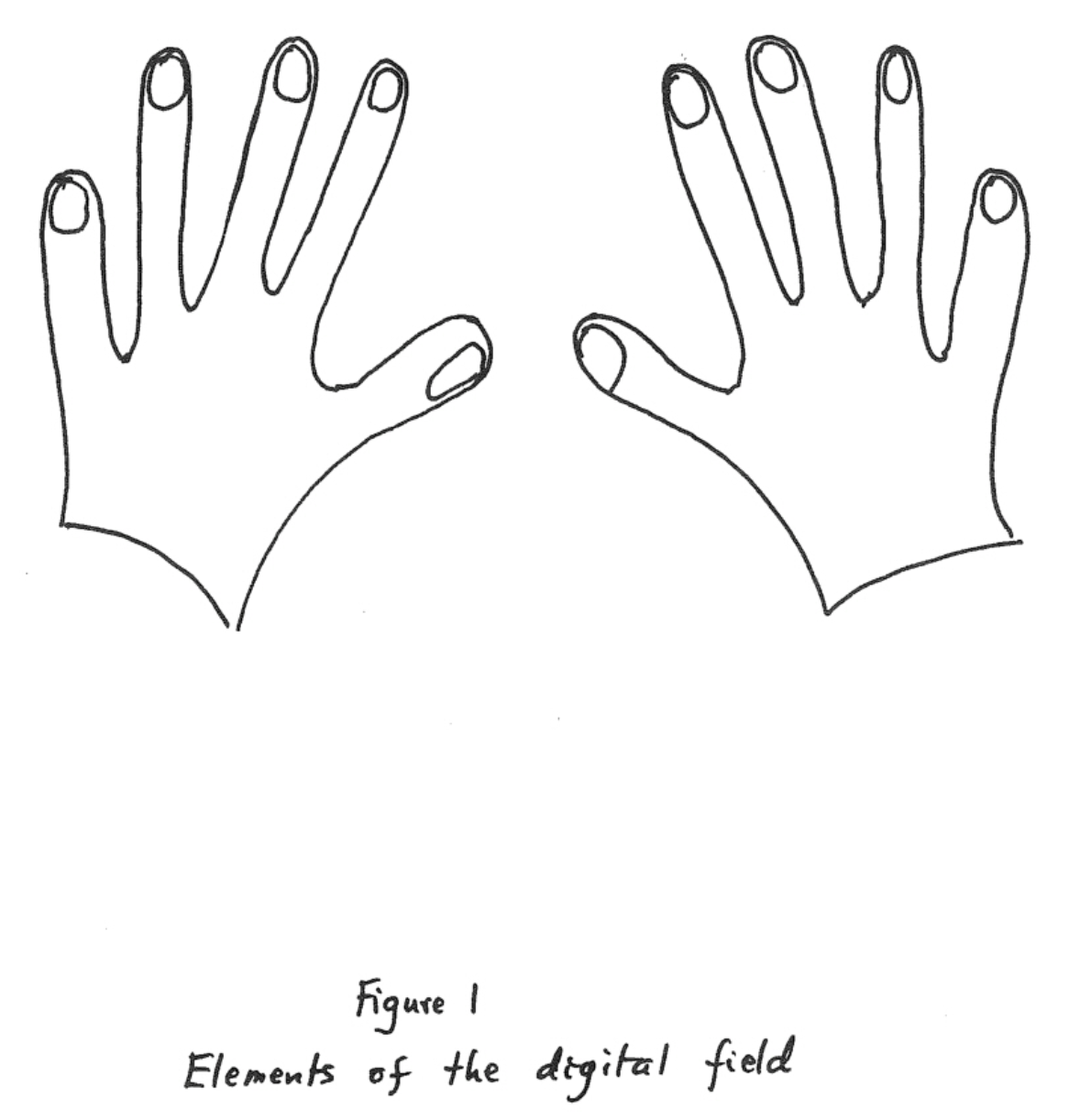

The elements of this digital field are shown in Fig. 1.

They are labelled $Left_1, Left_2, \dots, Left_5, Right_1, \dots, Right_5$ in the natural ordering (reading from left to right).

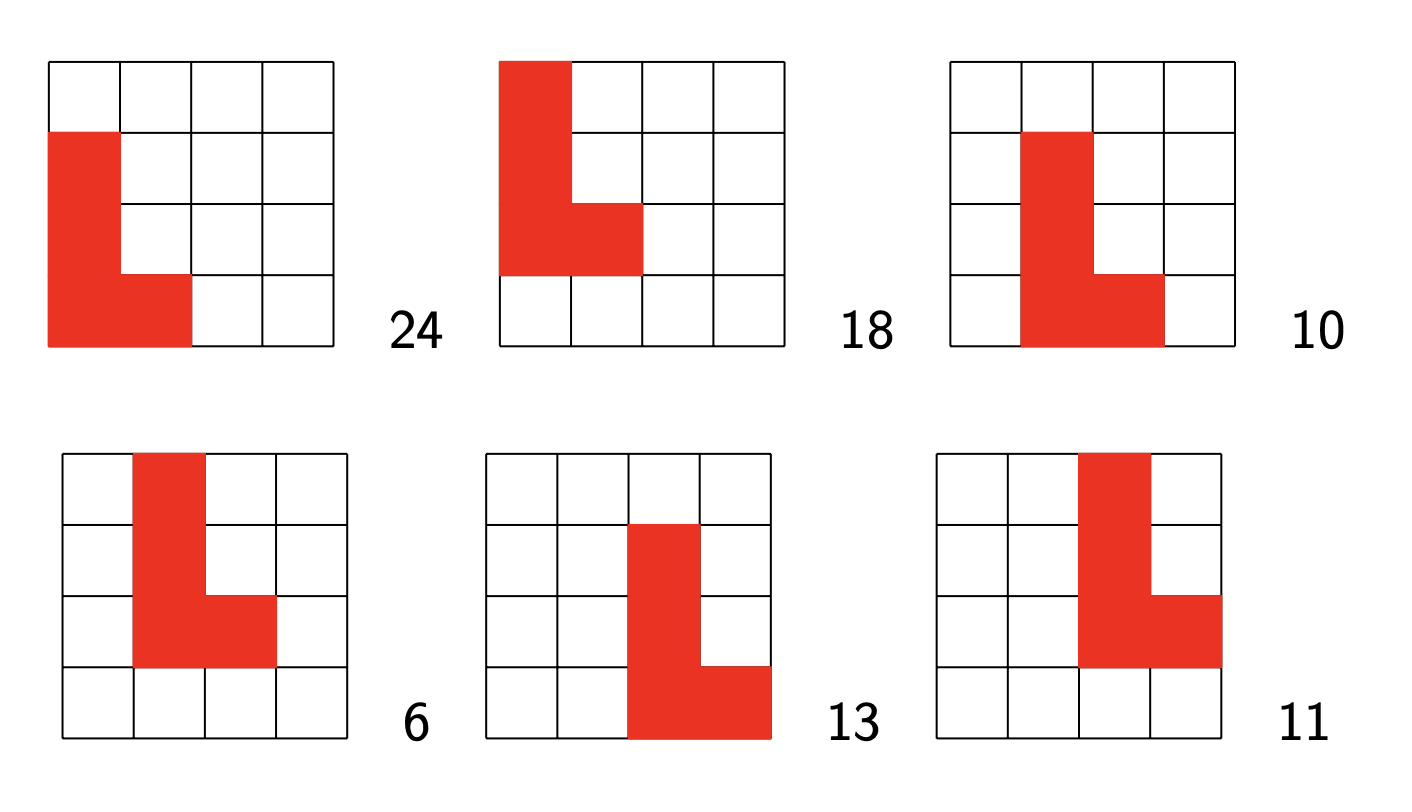

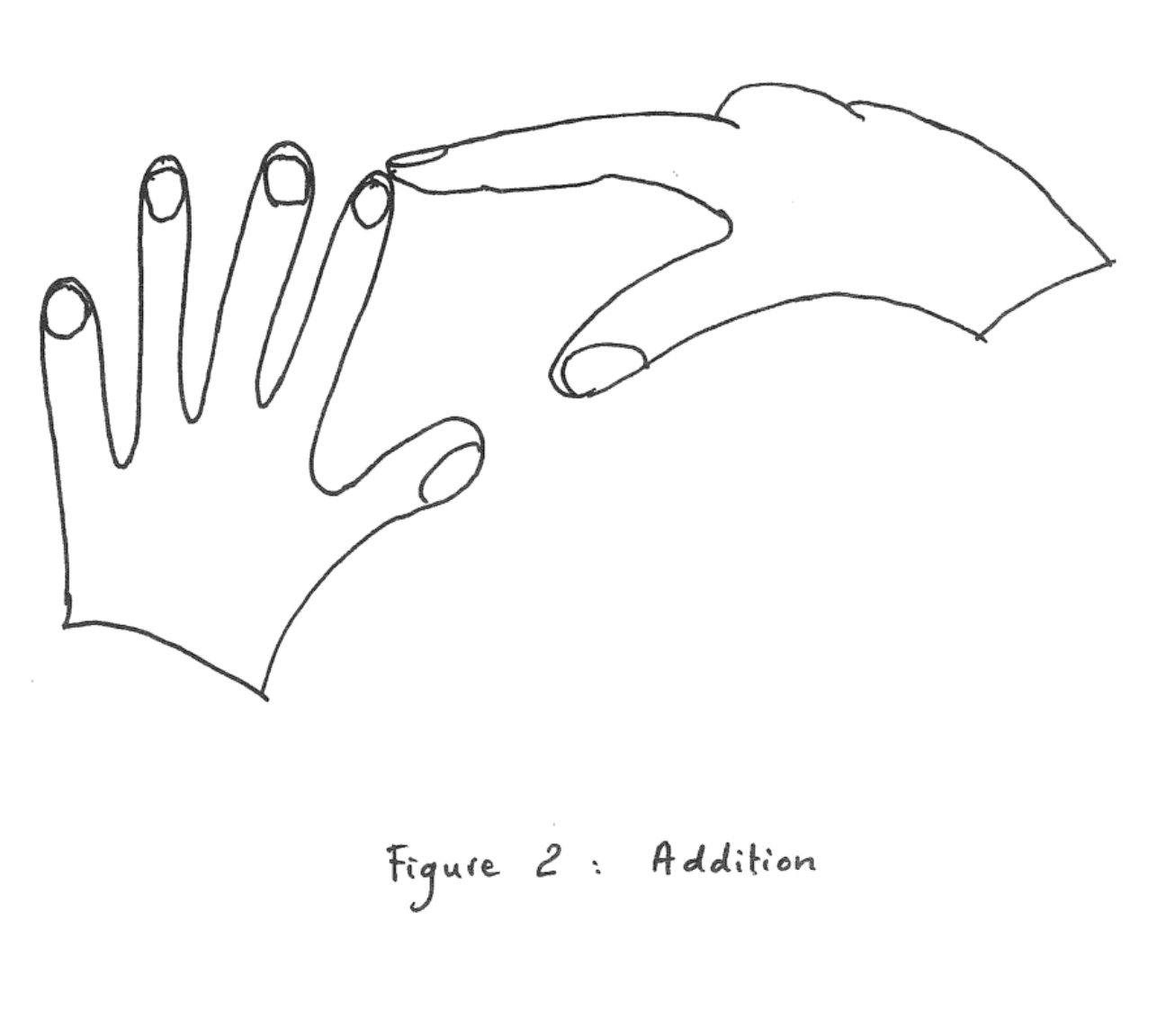

Addition is performed by counting, again in the natural way. An example is shown in Fig. 2, and for further details the reader can consult any kindergarten student.

In all digital systems the rules for multiplication can be written down immediately once addition has been defined; for example $2 \times n = n+n$. The reader will easily verify the rest of the details.

Since this field plainly contains ten elements (see Fig. 1) we conclude that there is a projective plain of order ten.

So far, the transcript.

More seriously now, the non-existence of a projective plane of order ten was only established in 1988, heavily depending on computer-calculations. A nice account is given in

C. M. H. Lam, “The Search for a Finite Projective Plane of Order 10”.

Now that recent iPhones nearly have the computing powers of former Cray’s, one might hope for easier proofs.

Fortunately, such a proof now exists, see A SAT-based Resolution of Lam’s Problem by Curtis Bright, Kevin K. H. Cheung, Brett Stevens, Ilias Kotsireas, Vijay Ganesh

David Roberts, aka the HigherGeometer, did a nice post on this

No order-10 projective planes via SAT.