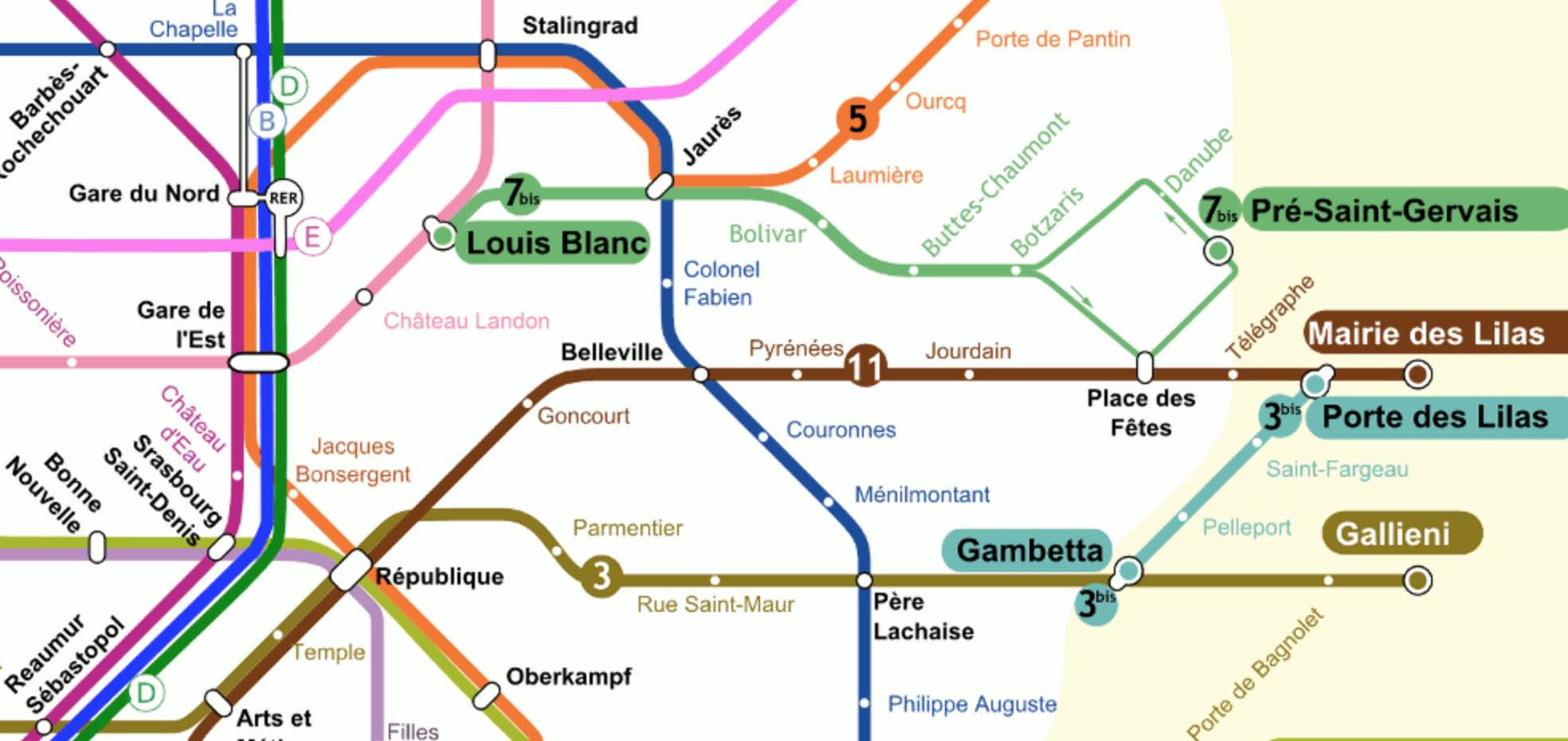

In the strange logic of subways I’ve used a small part of the Parisian metro-map to illustrate some of the bi-Heyting operations on directed graphs.

Little did I know that this metro-map gives only a partial picture of the underground network. The Parisian metro has several ghost stations, that is, stations that have been closed to the public and are no longer used in commercial service. One of these is the Haxo metro station.

Haxo metro station – Photo Credit

The station is situated on a line which was constructed in the 1920s between Porte des Lilas (line 3bis) and Pré-Saint-Gervais (line 7bis), see light and dark green on the map above . A single track was built linking Place des Fêtes to Porte des Lilas, known as la voie des Fêtes, with one intermediate station, Haxo.

For traffic in the other direction, another track was constructed linking Porte des Lilas to Pré Saint-Gervais, with no intermediate station, called la voie navette. Haxo would have been a single-direction station with only one platform.

But, it was never used, and no access to street level was ever constructed. Occasional special enthusiast trains call at Haxo for photography.

Apart from the Haxo ‘station morte’ (dead station), these maps show another surprise, a ‘quai mort’ (dead platform) known as Porte des Lilas – Cinema. You can hire this platform for a mere 200.000 Euro/per day for film shooting.

For example, Le fabuleux destin d’Amelie Poulin has a scene shot there. In the film the metro station is called ‘Abbesses’ (3.06 into the clip)

There is a project to re-open the ghost station Haxo for public transport. From a mathematical perspective, this may be dangerous.

Remember the subway singularity?

In the famous story A subway named Mobius by A. J. Deutsch, the Boylston shuttle on the Boiston subway went into service on March 3rd, tying together the seven principal lines, on four different levels. A day later, train 86 went missing on the Cambridge-Dorchester line…

The Harvard algebraist R. Tupelo suggested the train might have hit a node, a singularity. By adding the Boylston shuttle, the connectivity of the subway system had become infinite…

Now that we know of the strange logic of subways, an alternative explanation of this accident might be that by adding the Boylston shuttle, the logic of the Boston subway changed dramatically.

This can also happen in Paris.

I know, I’ve linked already to the movie ‘Moebius’ by Gustavo Mosquera, based on Deutsch’s story, set in Buenos Aires.

But, if you have an hour to spend, here it is again.

Comments closed