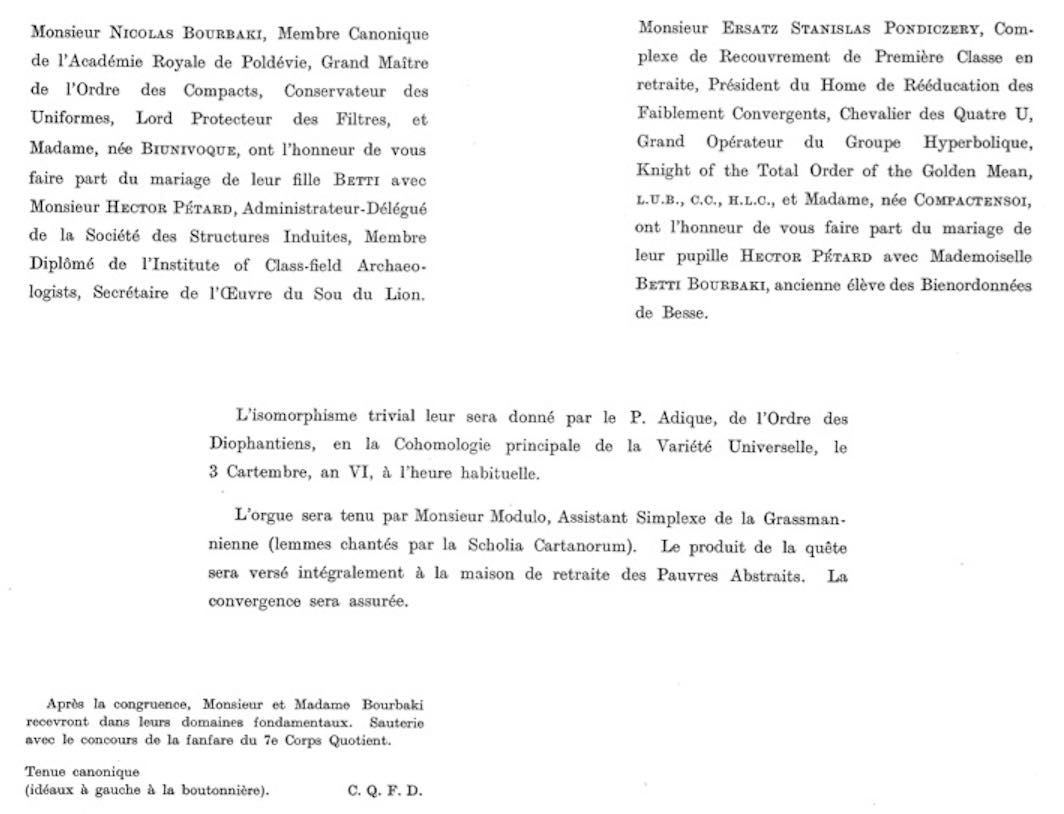

Stairways feature prominently in several drawings by Maurits Cornelis (“Mauk”) Escher, for example in this lithograph print Relativity from 1953.

Relativity (M. C. Escher) – Photo Credit

From its Wikipedia page:

In the world of ‘Relativity’, there are three sources of gravity, each being orthogonal to the two others.

Each inhabitant lives in one of the gravity wells, where normal physical laws apply.

There are sixteen characters, spread between each gravity source, six in one and five each in the other two.

The apparent confusion of the lithograph print comes from the fact that the three gravity sources are depicted in the same space.

The structure has seven stairways, and each stairway can be used by people who belong to two different gravity sources.

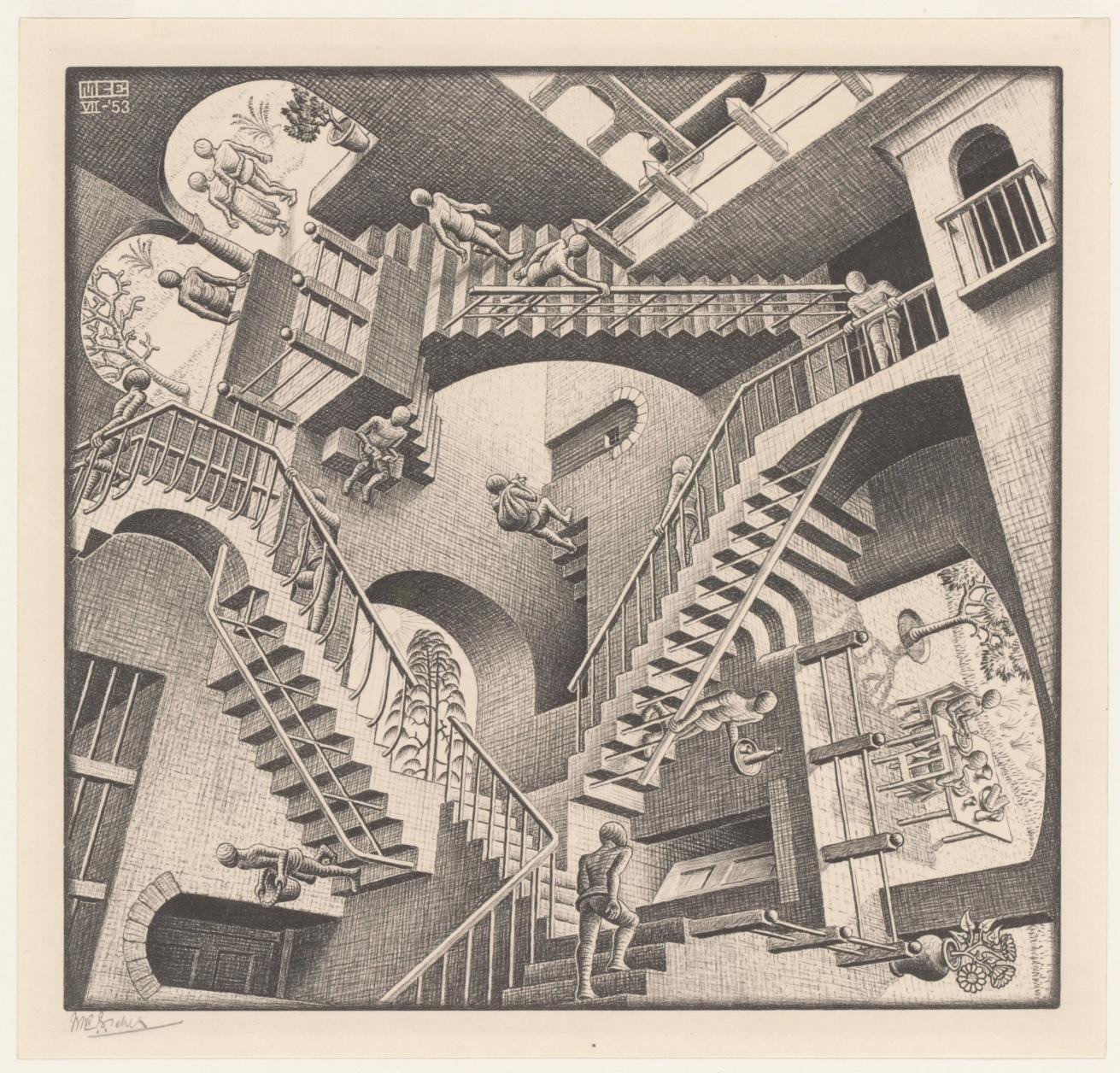

Escher’s inspiration for “Relativity” (h/t Gerard Westendorp on Twitter) were his recollections of the staircases in his old secondary school in Arnhem, the Lorentz HBS.

The name comes from the Dutch physicist and Nobel prize winner Hendrik Antoon Lorentz who attended from 1866 to 1869, the “Hogere Burger School” in Arnhem, then at a different location (Willemsplein).

Stairways Lorentz HBS in Arnhem – Photo Credit

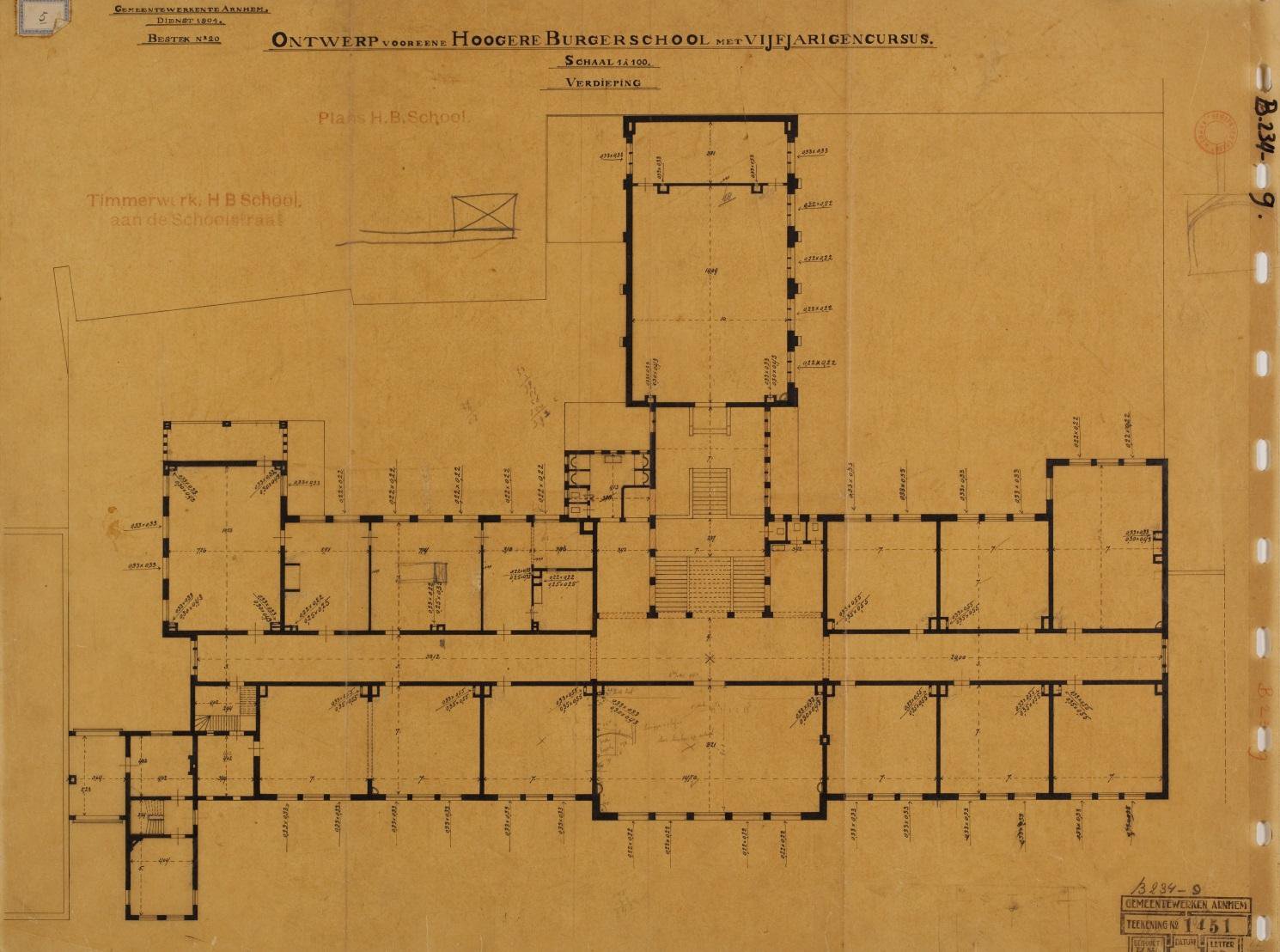

Between 1912 and 1918 Mauk Escher attended the Arnhem HBS, located in the Schoolstraat and build in 1904-05 by the architect Gerrit Versteeg. The school building is constructed around a monumental central stairway.

Arnhem HBS – G. Versteeg 1904-05 – Photo Credit

Plan HBS-Arnhem by G. Versteeg – Photo Credit

If you flip the picture below in the vertical direction, the two side-stairways become accessible to figures living in an opposite gravitation field.

Central staircase HBS Arnhem – Photo Credit

There’s an excellent post on the Arnhem-years of Mauk Escher by Pieter van der Kuil. Unfortunately (for most of you) in Dutch, but perhaps Google translate can do its magic here.

Comments closed