This week, I was hit hard by synchronicity.

Lately, I’ve been reading up a bit on psycho-analysis, tried to get through Grothendieck’s La clef des songes (the key to dreams) and I’m in the process of writing a series of blogposts on how to construct a topos of the unconscious.

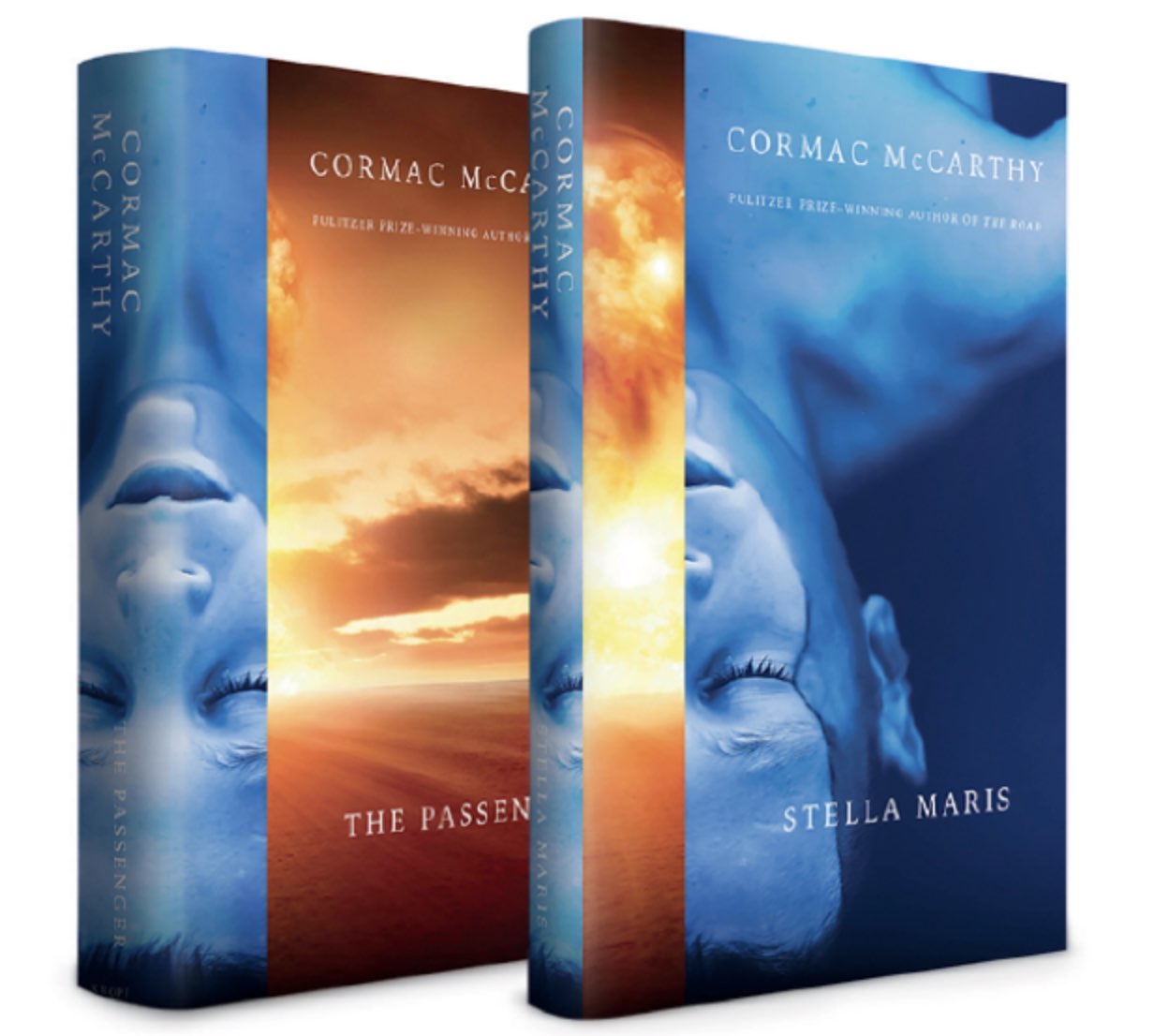

And then I read Cormac McCarthy‘s novels The passenger and Stella Maris, and got hit.

Stella Maris is set in 1972, when the math-prodigy Alicia Western, suffering from hallucinations, admits herself to a psychiatric hospital, carrying a plastic bag containing forty thousand dollars. The book consists entirely of dialogues, the transcripts of seven sessions with her psychiatrist Dr. Cohen (nomen est omen).

Alicia is a doctoral candidate at the University Of Chicago who got a scholarship to visit the IHES to work with Grothendieck on toposes.

During the psychiatric sessions, they talk on a wide variety of topics, including the nature of mathematics, quantum mechanics, music theory, dreams, and the unconscious (and its role in doing mathematics).

The core question is not how you do math but how does the unconscious do it. How it is that it’s demonstrably better at it than you are? You work on a problem and then you put it away for a while. But it doesnt go away. It reappears at lunch. Or while you’re taking a shower. It says: Take a look at this. What do you think? Then you wonder why the shower is cold. Or the soup. Is this doing math? I’m afraid it is. How is it doing it? We dont know. How does the unconscious do math? (page 99)

Before going to the IHES she had to send Grothendieck a paper (‘It was an explication of topos theory that I thought he probably hadn’t considered.’ page 136, and ‘while it proved three problems in topos theory it then set about dismantling the mechanism of the proofs.’ page 151). At the IHES ‘I met three men that I could talk to: Grothendieck, Deligne, and Oscar Zariski.’ (page 136).

I don’t know whether Zariski visited the IHES in the early 70ties, and while most historical allusions (to Grothendieck’s life, his role in Bourbaki etc.) are correct, Alicia mentions the ‘Langlands project’ (page 66) which may very well have been the talk of town at the IHES in 1972, but the mention of Witten ‘Grothendieck writes everything down. Witten nothing.’ (page 100) raised an eyebrow.

The book also contains these two nice attempts to capture some of the essence of topos theory:

When you get to topos theory you are at the edge of another universe.

You have found a place to stand where you can look back at the world from nowhere. It’s not just some gestalt. It’s fundamental. (page 13)

You asked me about Grothendieck. The topos theory he came up with is a witches’ brew of topology and algebra and mathematical logic.

It doesnt even have a clear identity. The power of the theory is still speculative. But it’s there.

You have a sense that it is waiting quietly with answers to questions that nobody has asked yet. (page 68)

I did read ‘The passenger’ first, which is probably better as then you’d know already some of the ghosts haunting Alicia, but it’s not a must if you are only interested in their discussions about the nature of mathematics. Be warned that it is a pretty dark book, better not read when you’re already feeling low, and it should come with a link to a suicide prevention line.

Here’s a more considered take on Stella Maris:

3 Comments