We have seen that John Conway defined a nim-addition and nim-multiplication on the ordinal numbers in such a way that the subfield $[\omega^{\omega^{\omega}}] \simeq \overline{\mathbb{F}}_2 $ is the algebraic closure of the field on two elements. We’ve also seen how to do actual calculations in that field provided we can determine the mystery elements $\alpha_p $, which are the smallest ordinals not being a p-th power of ordinals lesser than $[\omega^{\omega^{k-1}}] $ if $p $ is the $k+1 $-th prime number.

We have seen that John Conway defined a nim-addition and nim-multiplication on the ordinal numbers in such a way that the subfield $[\omega^{\omega^{\omega}}] \simeq \overline{\mathbb{F}}_2 $ is the algebraic closure of the field on two elements. We’ve also seen how to do actual calculations in that field provided we can determine the mystery elements $\alpha_p $, which are the smallest ordinals not being a p-th power of ordinals lesser than $[\omega^{\omega^{k-1}}] $ if $p $ is the $k+1 $-th prime number.

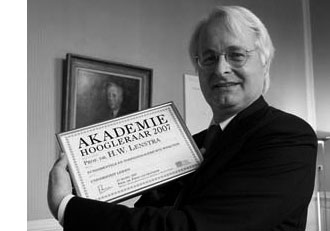

Hendrik Lenstra came up with an effective method to compute these elements $\alpha_p $ requiring a few computations in certain finite fields. I’ll give a rundown of his method and refer to his 1977-paper “On the algebraic closure of two” for full details.

For any ordinal $\alpha < \omega^{\omega^{\omega}} $ define its degree $d(\alpha) $ to be the degree of minimal polynomial for $\alpha $ over $\mathbb{F}_2 = [2] $ and for each prime number $p $ let $f(p) $ be the smallest number $h $ such that $p $ is a divisor of $2^h-1 $ (clearly $f(p) $ is a divisor of $p-1 $).

In the previous post we have already defined ordinals $\kappa_{p^k}=[\omega^{\omega^{k-1}.p^{n-1}}] $ for prime-power indices, but we now need to extend this definition to allow for all indices. So. let $h $ be a natural number, $p $ the smallest prime number dividing $h $ and $q $ the highest power of $p $ dividing $h $. Let $g=[h/q] $, then Lenstra defines

$\kappa_h = \begin{cases} \kappa_q~\text{if q divides}~d(\kappa_q)~\text{ and} \\ \kappa_g + \kappa_q = [\kappa_g + \kappa_q]~\text{otherwise} \end{cases} $

With these notations, the main result asserts the existence of natural numbers $m,m’ $ such that

$\alpha_p = [\kappa_{f(p)} + m] = [\kappa_{f(p)}] + m’ $

Now, assume by induction that we have already determined the mystery numbers $\alpha_r $ for all odd primes $r < p $, then by teh argument of last time we can effectively compute in the field $[\kappa_p] $. In particular, we can compute for every element its multiplicative order $ord(\beta) $ and therefore also its degree $d(\beta) $ which has to be the smallest number $h $ such that $ord(\beta) $ divides $[2^h-1] $.

Then, by the main result we only have to determine the smallest number m such that $\beta = [\kappa_{f(p)} +m] $ is not a p-th power in $\kappa_p $ which is equivalent to the condition that

$\beta^{(2^{d(\beta)}-1)/p} \not= 1 $ if $p $ divides $[2^{d(\beta)}-1] $

All these conditions can be verified within suitable finite fields and hence are effective. In this manner, Lenstra could extend Conway’s calculations (probably using a home-made finite field program running on a slow 1977 machine) :

[tex]\begin{array}{c|c|c} p & f(p) & \alpha_p \\ \hline 3 & 2 & [2] \\ 5 & 4 & [4] \\ 7 & 3 & [\omega]+1 \\ 11 & 10 & [\omega^{\omega}]+1 \\ 13 & 12 & [\omega]+4 \\ 17 & 8 & [16] \\ 19 & 18 & [\omega^3]+4 \\ 23 & 11 & [\omega^{\omega^3}]+1 \\ 29 & 28 & [\omega^{\omega^2}]+4 \\ 31 & 5 & [\omega^{\omega}]+1 \\ 37 & 36 & [\omega^3]+4 \\ 41 & 20 & [\omega^{\omega}]+1 \\ 43 & 14 & [\omega^{\omega^2}]+ 1 \end{array}[/tex]

Right, so let’s try the case $p=47 $. To begin, $f(47)=23 $ whence we have to determine the smallest field containg $\kappa_{23} $. By induction (Lenstra’s tabel) we know already that

$\kappa_{23}^{23} = \kappa_{11} + 1 = [\omega^{\omega^3}]+1 $ and $\kappa_{11}^{11} = \kappa_5 + 1 = [\omega^{\omega}]+1 $ and $\kappa_5^5=[4] $

Because the smallest field containg $4 $ is $[16]=\mathbb{F}_{2^4} $ we have that $\mathbb{F}_2(4,\kappa_5,\kappa_{11}) \simeq \mathbb{F}_{2^{220}} $. We can construct this finite field, together with a generator $a $ of its multiplicative group in Sage via

sage: f1.< a >=GF(2^220)

In this field we have to pinpoint the elements $4,\kappa_5 $ and $\kappa_{11} $. As $4 $ has order $15 $ in $\mathbb{F}_{2^4} $ we know that $\kappa_5 $ has order $75 $. Hence we can take $\kappa_5 = a^{(2^{220}-1)/75} $ and then $4=\kappa_5^5 $.

If we denote $\kappa_5 $ by x5 we can obtain $\kappa_{11} $ as x11 by the following sage-commands

sage: c=x5+1

sage: x11=c.nth_root(11)

It takes about 7 minutes to find x11 on a 2.4 GHz MacBook. Next, we have to set up the field extension determined by $\kappa_{23} $ (which we will call x in sage). This is done as follows

sage: p1.

sage: f=x^23-x11-1

sage: F2=f1.extension(f,'u')

The MacBook needed 8 minutes to set up this field which is isomorphic to $\mathbb{F}_{2^{5060}} $. The relevant number is therefore $n=\frac{2^{5060}-1}{47} $ which is the gruesome

34648162040462867047623719793206539850507437636617898959901744136581<br/>

259144476645069239839415478030722644334257066691823210120548345667203443<br/>

317743531975748823386990680394012962375061822291120459167399032726669613

<br/>

442804392429947890878007964213600720766879334103454250982141991553270171

938532417844211304203805934829097913753132491802446697429102630902307815

301045433019807776921086247690468136447620036910689177286910624860871748

150613285530830034500671245400628768674394130880959338197158054296625733

206509650361461537510912269982522844517989399782602216622257291361930850

885916974186835958466930689748400561295128553674118498999873244045842040

080195019701984054428846798610542372150816780493166669821114184374697446

637066566831036116390063418916814141753876530004881539570659100352197393

997895251223633176404672792711603439161147155163219282934597310848529360

118189507461132290706604796116111868096099527077437183219418195396666836

014856037176421475300935193266597196833361131333604528218621261753883518

667866835204501888103795022437662796445008236823338104580840186181111557

498232520943552183185687638366809541685702608288630073248626226874916669

186372183233071573318563658579214650042598011275864591248749957431967297

975078011358342282941831582626985121760847852546207377440873367589369439

085660784239080183415569559585998884824991911321095149718147110882474280

968166266224151511519773175933506503369761671964823112231808283557885030

984081329986188655169245595411930535264918359325712373064120338963742590

76555755141425

Remains ‘only’ to take x,x+1,etc. to the n-th power and verify which is the first to be unequal to 1. For this it is best to implement the usual powering trick (via digital expression of the exponent) in the field F2, something like

sage: def power(e,n):

...: le=n.bits()

...: v=n.digits()

...: mn=F2(e)

...: out=F2(1)

...: i=0

...: while i< le :

...: if v[i]==1 : out=F2(out_mn)

...: m=F2(mn_mn)

...: mn=F2(m)

...: i=i+1

...: return(out)

...:

then it takes about 20 seconds to verify that power(x,n)=1 but that power(x+1,n) is NOT! That is, we just checked that $\alpha_{47}=\kappa_{11}+1 $.

It turns out that 47 is the hardest nut to crack, the following primes are easier. Here’s the data (if I didn’t make mistakes…)

[tex]\begin{array}{c|c|c} p & f(p) & \alpha_p \\ \hline 47 & 23 & [\omega^{\omega^{7}}]+1 \\ 53 & 52 & [\omega^{\omega^4}]+1 \\ 59 & 58 & [\omega^{\omega^8}]+1 \\ 61 & 60 & [\omega^{\omega}]+[\omega] \\ 67 & 66 & [\omega^{\omega^3}]+[\omega] \end{array}[/tex]

It seems that Magma is substantially better at finite field arithmetic, so if you are lucky enough to have it you’ll have no problem finding $\alpha_p $ for all primes less than 100 by the end of the day. If you do, please drop a comment with the results…