Sunday, January 28th 1940, Hamburg

Ernst Witt wants to get two papers out of his system because he knows he’ll have to enter the Wehrmacht in February.

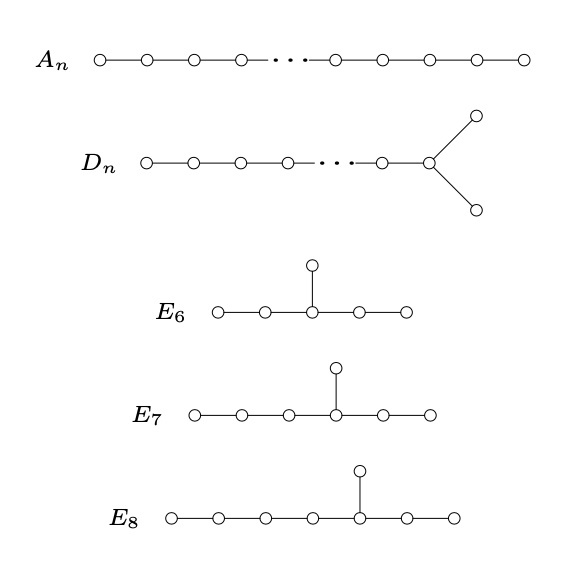

The first one, “Spiegelungsgruppen und Aufzählung halbeinfacher Liescher Ringe”, contains his own treatment of the root systems of semisimple Lie algebras and their reflexion groups, following up on previous work by Killing, Cartan, Weyl, van der Waerden and Coxeter.

(Photo: Natascha Artin, Nikolausberg 1933): From left to right: Ernst Witt; Paul Bernays; Helene Weyl; Hermann Weyl; Joachim Weyl, Emil Artin; Emmy Noether; Ernst Knauf; unknown woman; Chiuntze Tsen; Erna Bannow (later became wife of Ernst Witt)

Important for our story is that this paper contains the result stating that integral lattices generated by norm 2 elements are direct sums of root systems of the simply laced Dynkin diagrans $A_n, D_n$ and $E_6,E_7$ or $E_8$ (Witt uses a slightly different notation).

In each case, Witt knows of course the number of roots and the determinant of the Gram matrix

\[

\begin{array}{c|cc}

& \# \text{roots} & \text{determinant} \\

\hline

A_n & n^2+n & n+1 \\

D_n & 2n^2-2n & 4 \\

E_6 & 72 & 3 \\

E_7 & 126 & 2 \\

E_8 & 240 & 1

\end{array}

\]

The second paper “Eine Identität zwischen Modulformen zweiten Grades” proves that there are just two positive definite even unimodular lattices (those in which every squared length is even, and which have one point per unit volume, that is, have determinant one) in dimension sixteen, $E_8 \oplus E_8$ and $D_{16}^+$. Previously, Louis Mordell showed that the only unimodular even lattice in dimension $8$ is $E_8$.

The connection with modular forms is via their theta series, listing the number of lattice points of each squared length

\[

\theta_L(q) = \sum_{m=0}^{\infty} \#\{ \lambda \in L : (\lambda,\lambda)=m \} q^{m} \]

which is a modular form of weight $n/2$ ($n$ being the dimension which must be divisible by $8$) in case $L$ is a positive definitive even unimodular lattice.

The algebra of all modular forms is generated by the Eisenstein series $E_2$ and $E_3$ of weights $4$ and $6$, so in dimension $8$ we have just one possible theta series

\[

\theta_L(q) = E_2^2 = 1+480 q^2+ 61920 q^4+ 1050240 q^6+ \dots \]

It is interesting to read Witt’s proof of his main result (Satz 3) in which he explains how he constructed the possible even unimodular lattices in dimension $16$.

He knows that the sublattice of $L$ generated by the $480$ norm two elements must be a direct sum of root lattices. His knowledge of the number of roots in each case tells him there are only two possibilities

\[

E_8 \oplus E_8 \qquad \text{and} \qquad D_{16} \]

The determinant of the Gram matrix of $E_8 \oplus E_8$ is one, so this one is already unimodular. The remaining possibility

\[

D_{16} = \{ (x_1,\dots,x_{16}) \in \mathbb{Z}^{16}~|~x_1+ \dots + x_{16} \in 2 \mathbb{Z} \} \]

has determinant $4$ so he needs to add further lattice points (necessarily contained in the dual lattice $D_{16}^*$) to get it unimodular. He knows the coset representatives of $D_{16}^*/D_{16}$:

\[

\begin{cases}

[0]=(0, \dots,0) &~\text{of norm $0$} \\

[1]=(\tfrac{1}{2},\dots,\tfrac{1}{2}) &~\text{of norm $4$} \\

[2]=(0,\dots,0,1) &~\text{of norm $1$} \\

[3]=(\tfrac{1}{2},\dots,\tfrac{1}{2},-\tfrac{1}{2}) &~\text{of norm $4$}

\end{cases}

\]

and he verifies that the determinant of $D_{16}^+=D_{16}+([1]+D_{16})$ is indeed one (btw. adding coset $[3]$ gives an isomorphic lattice). Witt calls this procedure to arrive at the correct lattices forced (‘zwangslaufig’).

So, how do you think Witt would go about finding even unimodular lattices in dimension $24$?

To me it is clear that he would start with a direct sum of root lattices whose dimensions add up to $24$, compute the determinant of the Gram matrix and, if necessary, add coset classes to arrive at a unimodular lattice.

Today we would call this procedure ‘adding glue’, after Martin Kneser, who formalised this procedure in 1967.

On January 28th 1940, Witt writes that he found more than $10$ different classes of even unimodular lattices in dimension $24$ (without giving any details) and mentioned that the determination of the total number of such lattices will not be entirely trivial (‘scheint nicht ganz leicht zu sein’).

The complete classification of all $24$ even unimodular lattices in dimension $24$ was achieved by Hans Volker Niemeier in his 1968 Ph.D. thesis “Definite quadratische Formen der Dimension 24 und Diskriminante 1”, under the direction of Martin Kneser. Naturally, these lattices are now known as the Niemeier lattices.

Which of the Niemeier lattices were known to Witt in 1940?

There are three obvious certainties: $E_8 \oplus E_8 \oplus E_8$, $E_8 \oplus D_{16}^+$ (both already unimodular, the second by Witt’s work) and $D_{24}^+$ with a construction analogous to the one of $D_{16}^+$.

To make an educated guess about the remaining Witt-Niemeier lattices we can do two things:

- use our knowledge of Niemeier lattices to figure out which of these Witt was most likely to stumble upon, and

- imagine how he would adapt his modular form approach in dimension $16$ to dimension $24$.

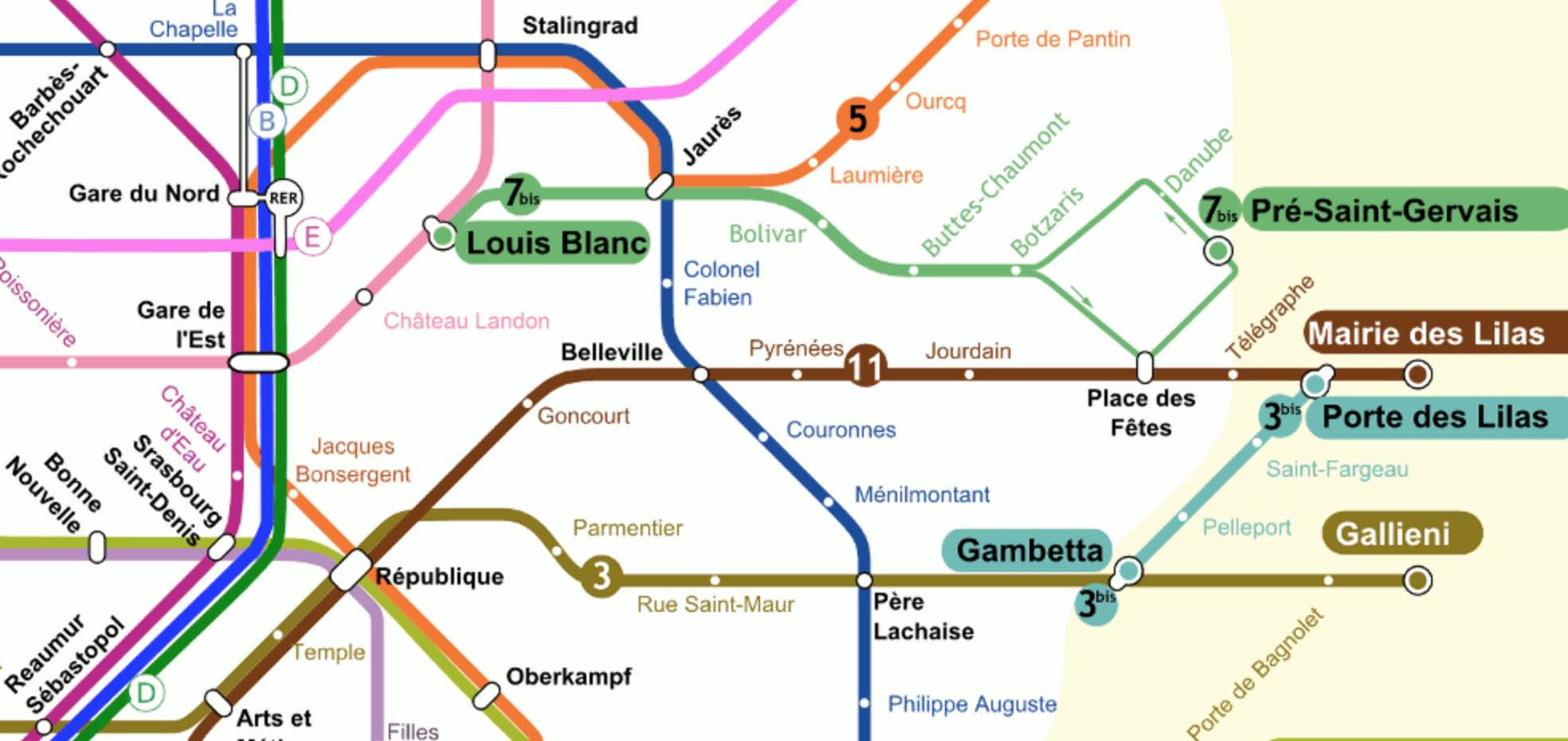

Here’s Kneser’s neighbourhood graph of the Niemeier lattices. Its vertices are the $24$ Niemeiers and there’s an edge between $L$ and $M$ whenever the intersection $L \cap M$ is of index $2$ in both $L$ and $M$. In this case, $L$ and $M$ are called neighbours.

Although the theory of neighbours was not known to Witt, the graph may give an indication of how likely it is to dig up a new Niemeier lattice by poking into an already discovered one.

The three certainties are the three lattices at the bottom of the neighborhood graph, making it more likely for the lattices in the lower region to be among Witt’s list.

For the other approach, the space of modular forms of weight $12$ is two dimensional, with a basis formed by the series

\[

\begin{cases}

E_6(q) = 1 + \tfrac{65520}{691}(q+2049 q^2 + 177148 q^3+4196353q^4+\dots \\

\Delta(q) = q-24 q^2+252q^3-1472q^4+ \dots

\end{cases}

\]

If you are at all with me, Witt would start with a lattice $R$ which is a direct sum of root lattices, so he would know the number of its roots (the norm $2$ vectors in $R$), let’s call this number $r$. Now, he wants to construct an even unimodular lattice $L$ containing $R$, so the theta series of both $L$ and $R$ must start off with $1 + r q^2 + \dots$. But, then he knows

\[

\theta_L(q) = E_6(q) + (r-\frac{65520}{691})\Delta(q) \]

and comparing coefficients of $\theta_L(q)$ with those of $\theta_R(q)$ will give him an idea what extra vectors he has to throw in.

If we’re generous to Witt (and frankly, why shouldn’t we), we may believe that he used his vast knowledge of Steiner systems (a few years earlier he wrote the definite paper on the Mathieu groups, and a paper on Steiner systems) to construct in this way the lattices $(A_1^{24})^+$ and $(A_2^{12})^+$.

The ‘glue’ for $(A_1^{24})^+$ is coming from the extended binary Golay code, which itself uses the Steiner system $S(5,8,24)$. $(A_2^{12})^+$ is constructed using the extended ternary Golay code, based on the Steiner system $S(5,6,12)$.

The one thing that would never have crossed his mind that sunday in 1940 was to explore the possibility of an even unimodular 24-dimensional lattice $\Lambda$ without any roots!

One with $r=0$, and thus with a theta series starting off as

\[

\theta_{\Lambda}(q) = 1 + 196560 q^4 + 16773120 q^6 + \dots \]

No, he did not find the Leech lattice that day.

If he would have stumbled upon it, it would have simply blown his mind.

It would have been so much against all his experiences and intuitions that he would have dropped everything on the spot to write a paper about it, or at least, he would have mentioned in his ‘more than $10$ lattices’-claim that, surprisingly, one of them was an even unimodular lattice without any roots.