Two more sources I’d like to draw from for this fall’s maths for designers-course:

1. Geometry and the Imagination

A fantastic collection of handouts for a two week summer workshop entitled ’Geometry and the Imagination’, led by John Conway, Peter Doyle, Jane Gilman and Bill Thurston at the Geometry Center in Minneapolis, June 1991, based on a course ‘Geometry and the Imagination’ they taught twice before at Princeton.

Among the goodies a long list of exercises in imagining (always useful to budding architects) and how to compute curvature by peeling potatoes and other vegetables…

The course really shines in giving a unified elegant classification of the 17 wallpaper groups, the 7 frieze groups and the 14 families of spherical groups by using Thurston’s concept of orbifolds.

If you think this will be too complicated, have a look at the proof that the orbifold Euler characteristic of any symmetry pattern in the plane with bounded fundamental domain is zero :

Take a large region in the plane that is topologically a disk (i.e. without holes). Its Euler characteristic is $1$. This is approximately equal to $N$ times the orbifold Euler characteristic for some large $N$, so the orbifold Euler characteristic must be $0$.

This then leads to the Orbifold Shop where they sell orbifold parts:

- a handle for 2 Euros,

- a mirror for 1 Euro,

- a cross-cap for 1 Euro,

- an order $n$ cone point for $(n-1)/n$ Euro,

- an order $n$ corner reflector for $(n-1)/2n$ Euro, if you have the required mirrors to install this piece.

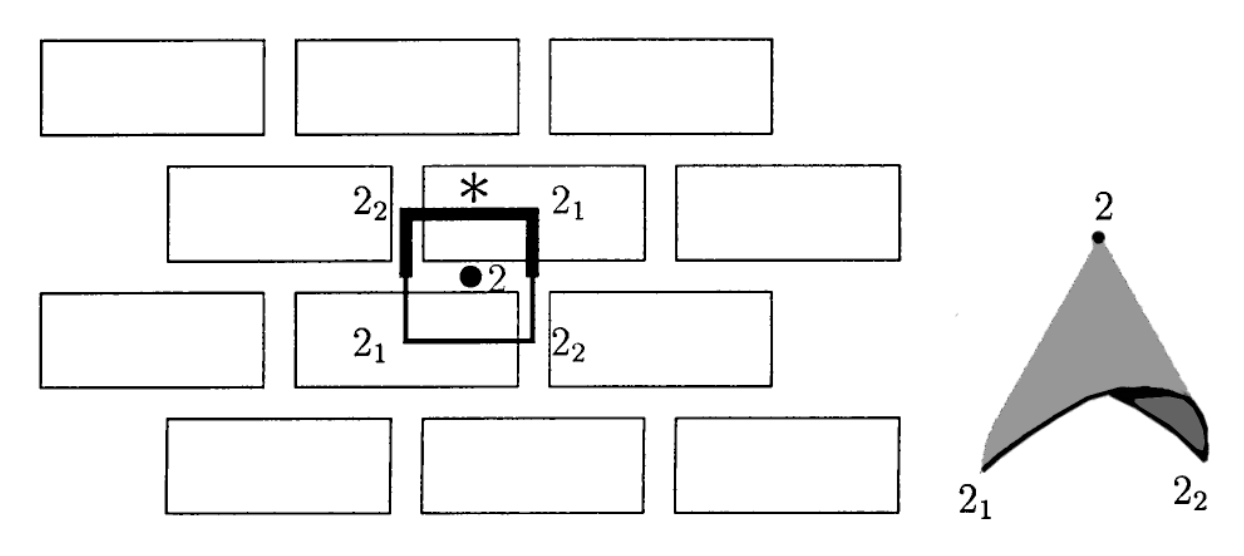

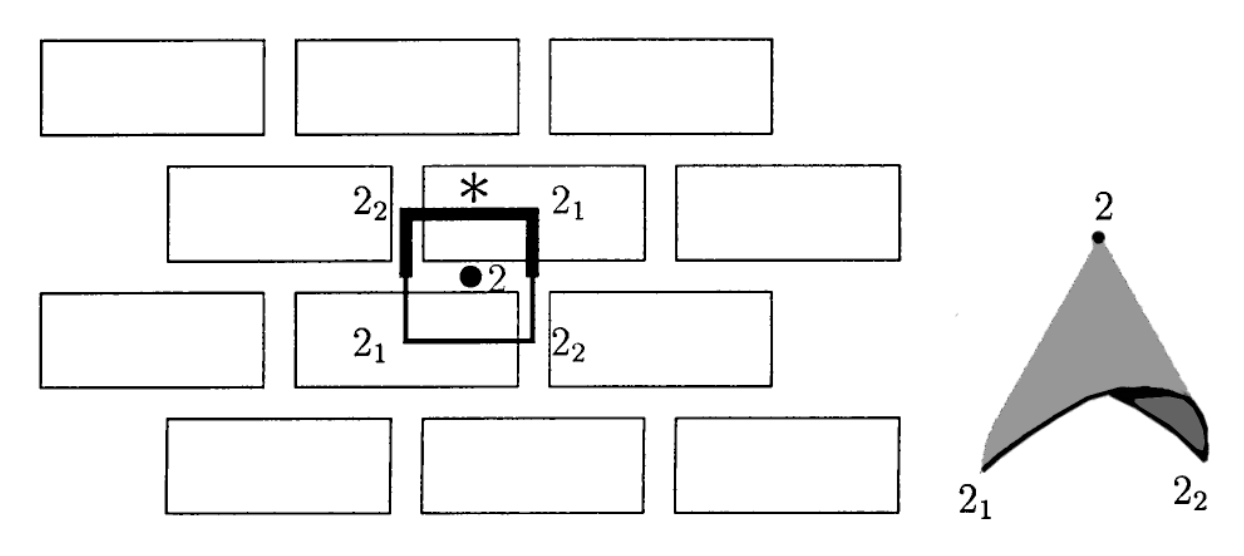

Here’s a standard brick wall, with its fundamental domain and corresponding orbifold made from a mirror piece (1 Euro), two order $2$ corner reflectors (each worth $.25$ Euro), and one order $2$ cone point (worth $.5$ Euro). That is, this orbifold will cost you exactly $2$ Euros.

If you spend exactly $2$ Euros at the Orbifold Shop (and there are $17$ different ways to do this), you will have an orbifold coming from a symmetry pattern in the plane with bounded fundamental domain, that is, one of the $17$ wallpaper patterns.

For the mathematicians among you desiring more details, please read The orbifold notation for two-dimensional groups by Conway and Daniel Huson, from which the above picture was taken.

2. On the Cohomology of Impossible Figures by Roger Penrose

The aspiring architect should be warned that some constructions are simply not possible in 3D, even when they look convincing on paper, such as Escher’s Waterfall.

M.C. Escher, Waterfall – Photo Credit

In his paper, Penrose gives a unified approach to debunk such drawings by using cohomology groups.

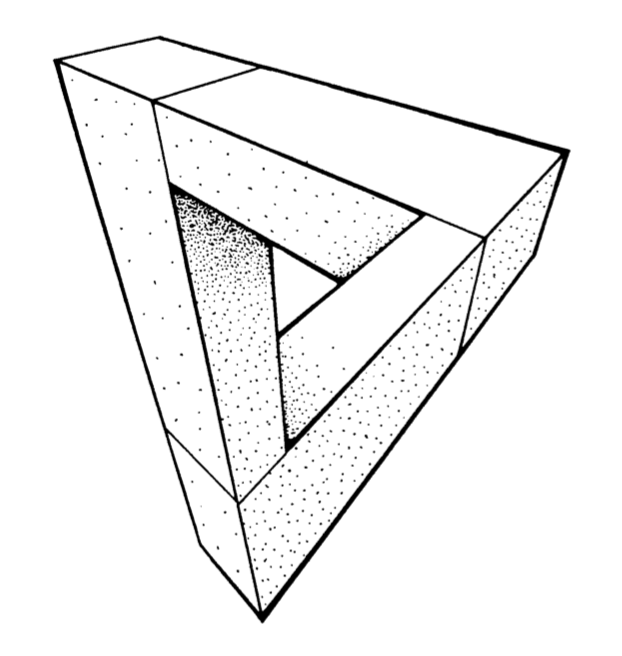

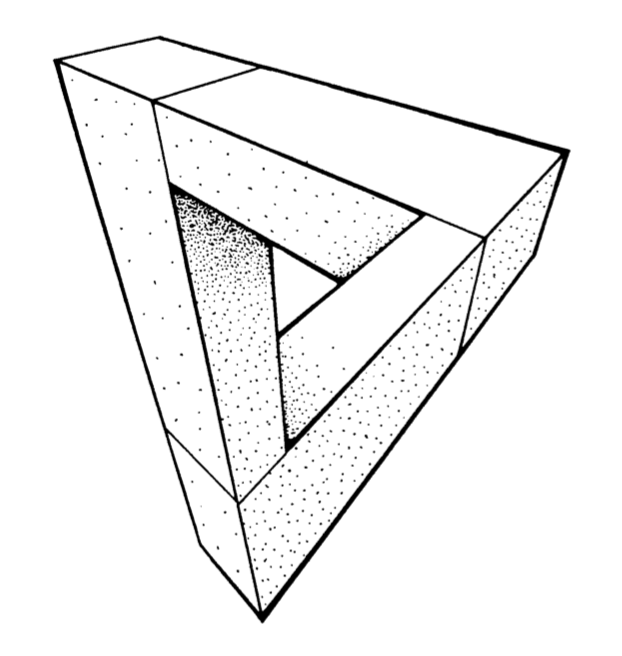

Clearly I have no desire to introduce cohomology, but it may still be possible to get the underlying idea across. Let’s take the Penrose triangle (all pictures below taken from Penrose’s paper)

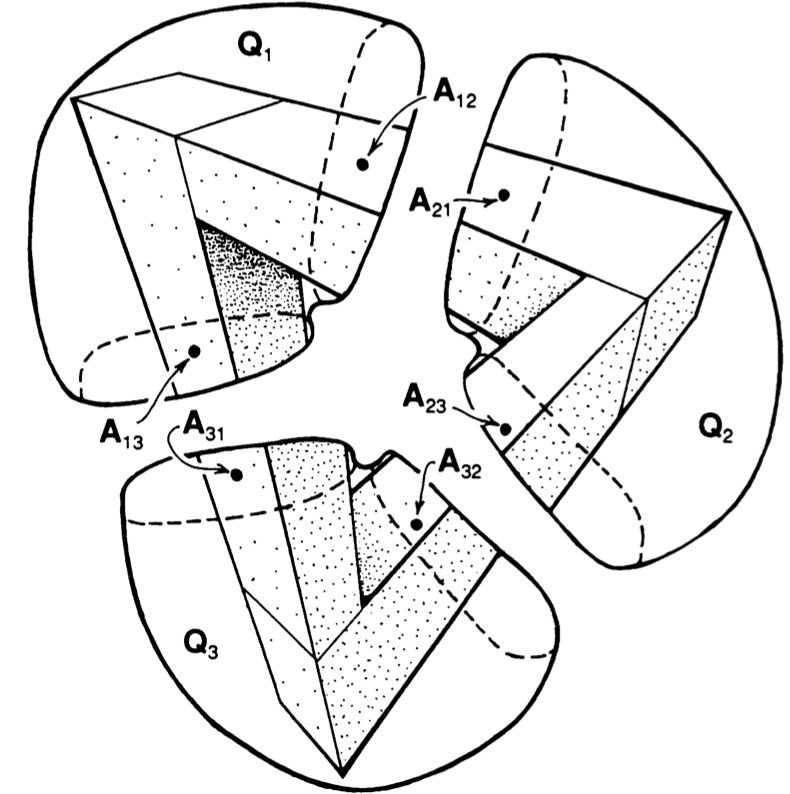

The idea is to break up such a picture in several parts, each of which we do know to construct in 3D (that is, we take a particular cover of our figure). We can slice up the Penrose triangle in three parts, and if you ever played with Lego you’ll know how to construct each one of them.

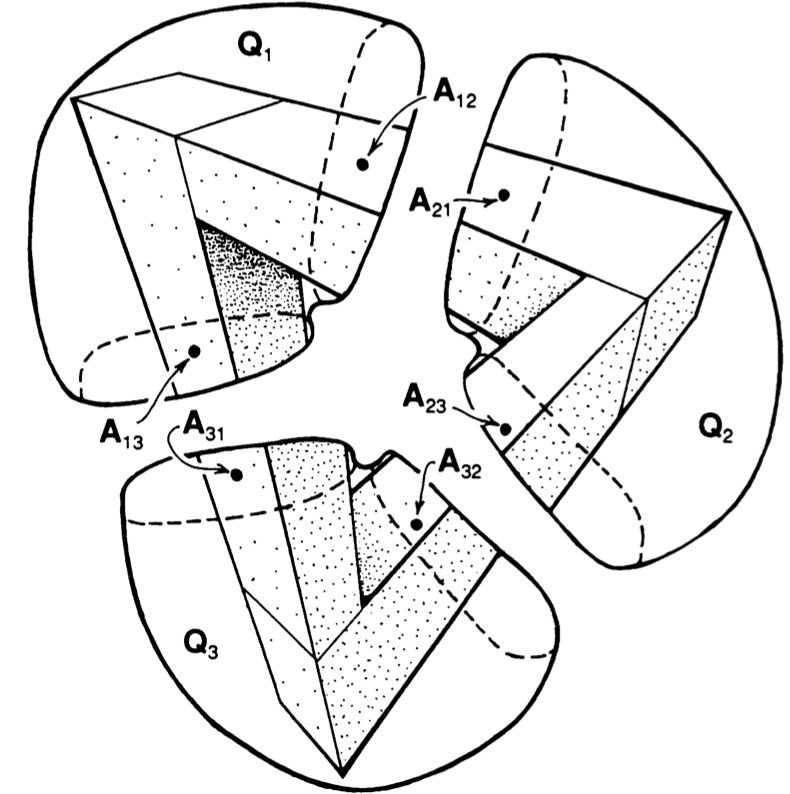

Next, position the constructed pieces in space as in the picture and decide which of the two ends is closer to you. In $Q_1$ it is clear that point $A_{12}$ is closer to you than $A_{13}$, so we write $A_{12} < A_{13}$.

Similarly, looking at $Q_2$ and $Q_3$ we see that $A_{23} < A_{21}$ and that $A_{31} < A_{32}$.

Next, if we try to reassemble our figure we must glue $A_{12}$ to $A_{21}$, that is $A_{12}=A_{21}$, and similarly $A_{23}=A_{32}$ and $A_{31}=A_{13}$. But, then we get

\[

A_{13}=A_{31} < A_{32}=A_{23} < A_{21}=A_{12} < A_{13} \]

which is clearly absurd.

Once again, if you have suggestions for more material to be included, please let me know.